Overview:

The War of 1812, often overshadowed in American historical memory by the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, was nevertheless crucial in shaping the young nation’s identity and international standing. Sparked by British restrictions on American trade, impressment of American sailors into the British Royal Navy, and territorial conflicts along the Canadian frontier, the war tested the resolve of the fledgling United States.

The Niagara Corridor:

During the War of 1812, few places saw as much sustained combat and strategic importance as the Niagara Corridor. This narrow stretch of land followed the Niagara River as it flowed north from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario, forming a natural boundary between the United States and British Canada. But more than a geographical feature, the corridor became one of the war’s most fiercely contested theaters—a vital artery for supply, movement, and invasion.

The terrain on either side of the river was dotted with key military outposts: Fort Niagara on the American side, Fort George across the river in Upper Canada, and numerous smaller fortifications and encampments in between. Whoever controlled this corridor had a direct route into the heart of Canada—or a buffer to stop an invasion cold.

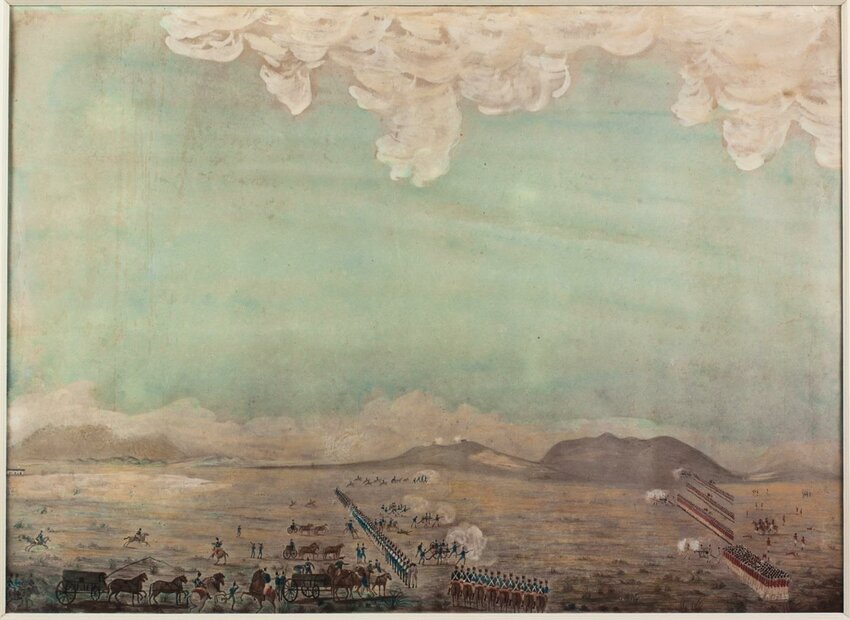

Throughout the conflict, both American and British forces launched major campaigns here. It became a revolving stage of advances, retreats, and bitterly fought battles. In 1812, the Americans suffered a stinging defeat at Queenston Heights, where British regulars and Canadian militia, reinforced by Mohawk warriors, repelled the first major U.S. invasion. The following spring, American forces launched a successful amphibious assault and captured Fort George, briefly securing a foothold in Canadian territory.

Fort George:

The capture of Fort George in May 1813 marked a key moment in the conflict. Situated along the western bank of the Niagara River, Fort George was a vital stronghold controlling access to Upper Canada. American forces, commanded by Major General Henry Dearborn and Brigadier General Winfield Scott, executed a meticulously planned amphibious assault on May 27, 1813. With support from naval artillery under Commodore Isaac Chauncey, approximately 4,000 American soldiers launched boats across the Niagara River under heavy cannon fire, storming the beaches near the fort.

British commander Brigadier General John Vincent defended the fort with about 1,400 soldiers. Despite determined resistance, overwhelming American artillery fire and coordinated infantry attacks forced the British into a strategic retreat, abandoning the fort. Fort George fell to American forces by midday, marking a significant tactical victory.

However, victory brought mixed consequences. American occupation lasted only briefly, becoming increasingly vulnerable to attacks from British regulars and Indigenous allies. Facing sustained pressure, American troops ultimately withdrew in December 1813, burning the town of Newark (modern-day Niagara-on-the-Lake) to deny shelter and supplies to the British. This controversial action provoked harsh retaliation: British forces crossed the river, capturing Fort Niagara in a surprise attack and subsequently burning towns along the American side, including Buffalo and Black Rock.

The burning of Niagara-on-the-Lake was a brutal reminder of the war’s harsh realities. Homes, stores, and public buildings were reduced to ashes in the depth of winter, leaving residents destitute and fueling bitterness between combatants. This act of destruction highlighted the vicious cycle of retaliation that characterized much of the war along the border.

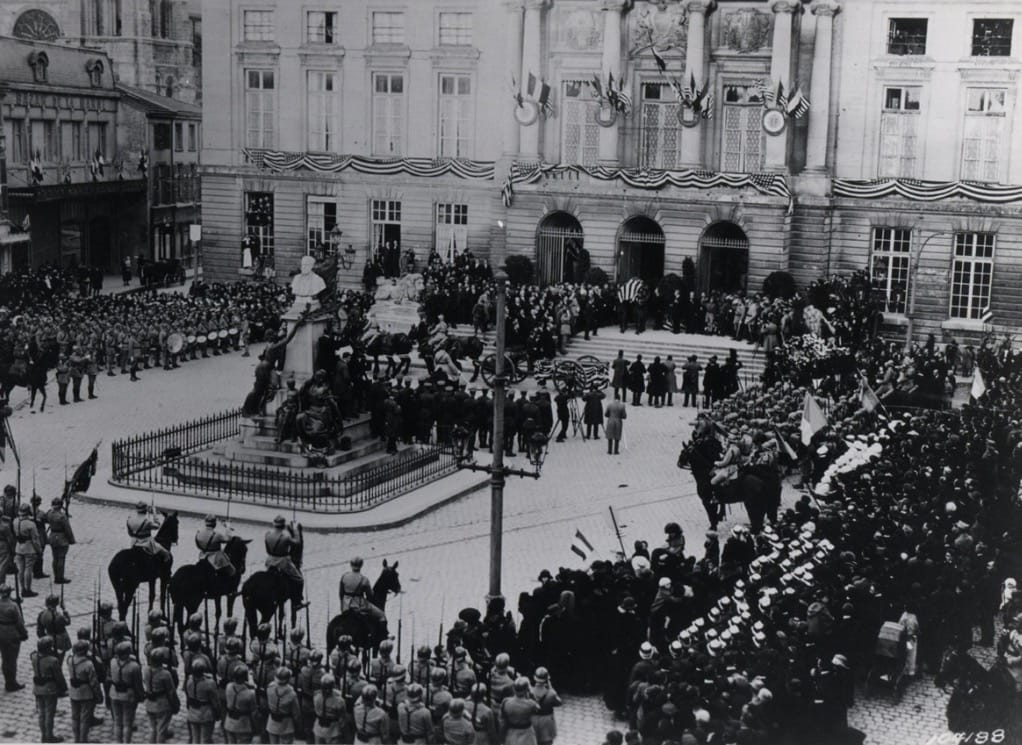

Ultimately, the capture of Fort George and the burning of Niagara-on-the-Lake exemplified the complexities and contradictions of the War of 1812: tactical victories yielding strategic challenges, and military successes overshadowed by severe consequences. Despite ending in stalemate with the Treaty of Ghent in 1814, the war fostered a profound sense of national unity in the United States and affirmed its sovereignty and resilience in the face of adversity.

Canadian Designated Viticultural Areas (DVAs)

Canada recognizes its wine-producing regions through a system known as Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA), a regulatory and appellation system that ensures quality and origin for Canadian wines. Much like the AOC in France or DOC in Italy, the VQA framework certifies that wines are made with grapes grown in specific geographic areas and meet rigorous production standards.

The system began in Ontario and British Columbia, the two largest wine-producing provinces. Each province administers its own VQA standards through governing bodies—VQA Ontario and the British Columbia Wine Authority—which oversee everything from vineyard location and grape varieties to winemaking practices and labeling.

Canada’s recognized wine regions are referred to as Designated Viticultural Areas (DVAs). These are legally defined geographic areas with distinct climates, soils, and topographies that influence the character of the wines. Within these DVAs are smaller sub-appellations, which allow even more precise identification of origin, especially in places like the Niagara Peninsula or Okanagan Valley, where microclimates vary dramatically over short distances.

For a wine to carry the VQA label, it must not only be made from 100% Canadian-grown grapes from approved varieties, but it must also pass sensory and laboratory testing to ensure it meets quality benchmarks. This guarantees a high level of transparency, traceability, and authenticity, helping both domestic and international consumers identify premium Canadian wines.

Through this system, Canada has carved out a growing international reputation, particularly for cool-climate varietals like Riesling, Pinot Noir, and Chardonnay—as well as its signature Icewine, which is strictly regulated under VQA guidelines to preserve its prestige and uniqueness.

Niagara-on-the-Lake:

Terrain and Soil:

Niagara-on-the-Lake lies at the northern end of the Niagara Peninsula in Ontario, Canada, where the Niagara River meets Lake Ontario. The region is uniquely positioned between two major bodies of water—Lake Ontario to the north and Lake Erie to the south—which moderate the climate and extend the growing season. The terrain is relatively flat with gentle slopes near the Escarpment and lake shore, providing excellent air drainage and frost protection. Soils are varied but generally consist of sandy loam, clay, and limestone-rich deposits left behind by ancient glacial activity—ideal for grapevine health and flavor development.

The area’s microclimate, shaped by lake breezes and the protection of the Niagara Escarpment, allows for the successful cultivation of delicate vinifera grapes, even at this northern latitude.

Grapes Grown:

Whites: Riesling, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, Gewürztraminer, Pinot Gris

Reds: Pinot Noir, Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Gamay Noir

Wines Produced:

Niagara-on-the-Lake is internationally celebrated for its Icewine, a sweet dessert wine made from naturally frozen grapes—especially Riesling and Vidal Blanc—that deliver intense flavors and high acidity. In addition to Icewine, the region produces award-winning dry table wines, including vibrant Rieslings, oaked and unoaked Chardonnays, and floral Sauvignon Blancs. On the red side, Pinot Noir and Cabernet Franc thrive, producing cool-climate wines with finesse, spice, and earthy notes. Merlot and Bordeaux-style blends have also gained traction due to increasingly warm summers and innovative vineyard management.

Historical Roots:

Wine production in Niagara-on-the-Lake began in earnest in the mid-19th century, about 50 years after the War of 1812, but the industry took root in the 1970s and 1980s when winemakers began planting Vitis vinifera (European grape varieties) instead of native or hybrid grapes. The region’s modern winemaking renaissance is largely credited to pioneers like Donald Ziraldo and Karl Kaiser, who founded Inniskillin in 1975 and helped secure the first winery license in Ontario since Prohibition. Their success with Icewine in the 1980s put Niagara-on-the-Lake on the international wine map.

Today, Niagara-on-the-Lake is one of Canada’s most recognized and visited wine regions, with over 20 wineries clustered within a compact, scenic area surrounded by orchards, vineyards, and historic sites. Its winemaking tradition is deeply tied to both its terroir and its evolving reputation for world-class cool-climate wines.

Niagara Escarpment AVA – to learn more about American Viticultural Areas (AVAs) see: https://vinibellum.com/mississippi-rifles-in-wine-country-the-skirmish-at-rancho-olompali#AVAs

Terrain and Soil:

The Niagara Escarpment AVA lies in western New York’s Niagara County, just across the river from Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario. Anchored by the limestone ridge that gives the region its name, the escarpment provides a natural elevation and drainage advantage, creating an ideal environment for viticulture. The terrain features gentle slopes and shallow valleys formed by glacial retreat, offering protection from spring frosts and maximizing sun exposure.

Soils in the region are predominantly glacial till with a mix of clay, loam, and limestone—similar to its Canadian counterpart. This well-drained, mineral-rich soil supports deep root penetration and enhances flavor concentration in grapes. The close proximity to Lake Ontario moderates temperatures, extending the growing season and reducing the risk of vine damage from extreme cold.

Grapes Grown:

- Whites: Riesling, Chardonnay, Gewürztraminer, Pinot Gris, Vidal Blanc

- Reds: Pinot Noir, Cabernet Franc, Merlot, Baco Noir, Chambourcin

Wines Produced:

The Niagara Escarpment AVA produces a range of expressive cool-climate wines. Riesling is a standout, yielding crisp, aromatic styles with bright acidity and stone fruit notes. Chardonnay is produced in both unoaked and barrel-aged forms, while Vidal Blanc is used for both table wine and Icewine-style dessert wines. On the red side, Cabernet Franc performs particularly well, with peppery, earthy characteristics and a lighter body. Baco Noir and Pinot Noir offer tart red fruit and spice, reflecting the region’s cool climate and short growing season.

Although small compared to other AVAs, the Niagara Escarpment is known for innovative, boutique wineries producing handcrafted wines with a strong sense of place. Sustainable practices and experimentation with hybrid varieties help wineries thrive in this challenging environment.

Historical Roots:

While grape growing in western New York dates back to the 19th century, much of the early production focused on Concord and Niagara grapes for juice and jelly. The shift toward fine wine began in the late 20th century, with small growers embracing vinifera and French-American hybrids suited to the region’s unique terroir. The AVA was officially recognized in 2005, helping to distinguish it from other parts of New York’s wine country and to emphasize its shared geology and climate with Ontario’s Niagara Peninsula.

Today, the Niagara Escarpment AVA is a rising star in American viticulture, offering high-quality cool-climate wines just minutes from the Canadian border. Its scenic vineyards, limestone-rich soils, and lake-moderated microclimate make it a compelling destination for wine lovers.

Weapon spotlight: 24-pound guns

In the spring of 1813, as American forces amassed at Fort Niagara, looming over British-held Fort George, they prepared for a bombardment that would mark a pivotal moment in the War of 1812. Central to this thunderous display were the formidable 24‑pounder guns—imposing smoothbore artillery pieces inherited from European naval and siege traditions.

Born from 18th-century European ordnance doctrine, the 24‑pound gun featured a 152 mm (6‑inch) bore, a barrel stretching nearly 9 ft, and weighing close to 2,500lbs. These warhorses of cannon‑firing were cast in iron, often tapped for naval service aboard frigates and ships of the line, and then repurposed on land during sieges.

Carriage and Aiming:

Mounted on robust wooden carriages, barbette or naval-style, the artillery pieces could be elevated and traversed via mechanical components: trunnions, elevating screws, traverse wheels, and axletrees. The mid-century manuals show just how precisely these elements supported heavy firepower while allowing the crew to pivot and adjust.

Operational Power at Fort George:

On the eve of battle, American gunners unloaded barrel after barrel of powder and hefty 24-pound iron shot across the Niagara. With each pounding volley, rumble of the barrels, and recoil soaked by sturdy carriages, the cannonade tore through British defenses with crushing force. This relentless bombardment shattered gun emplacements, silenced enemy batteries, and so weakened the fort’s walls that infantry could safely land and storm the position.

Though devastatingly effective, these massive iron guns came with limitations: immense weight hindered transport and emplacement, while their slow rate of fire made swift adjustments difficult. And while their rough early casting occasionally led to flaws, the lessons learned from their performance propelled future artillery development—ushering in innovations like lighter 24‑pounder howitzers, rifled gun-boats, and enhanced metallurgy via figures like Dahlgren and Sawyer by mid-century.

Summary

The capture of Fort George in May 1813 marked a key moment in the War of 1812, giving American forces temporary control over a strategic position in Upper Canada. Although the U.S. occupation was short-lived, the battle demonstrated the effectiveness of coordinated land and naval operations, especially the use of heavy artillery like the 24-pounder cannon. Today, the Niagara region is known more for its vineyards than its battlefields, but the legacy of the conflict remains visible in its preserved forts, rebuilt towns, and historical landmarks.

Sources:

Books:1

Websites:

American Battlefield Trust. “Fort Niagara.” War of 1812: Battles, American Battlefield Trust. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/war-1812/battles/fort-niagara.

Archives of Ontario. “The War of 1812: Niagara Frontier and York – 1813.” Archives of Ontario. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/explore/online/1812/niagara-1813.aspx.

Barbuto, Richard V. “The War of 1812 on the Niagara River.” Army Historical Foundation. Originally published approximately nine years ago. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://armyhistory.org/the-war-of-1812-on-the-niagara-river/.

Clements Library, University of Michigan. “Case 11: U.S. and British Camps—Niagara Frontier, War of 1812.” In The War of 1812, Clements Library. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://clements.umich.edu/exhibit/the-war-of-1812/case-11/.

Friends of Fort George. “History of Fort George.” Friends of Fort George (Niagara‑on‑the‑Lake). Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.friendsoffortgeorge.ca/fort-george/history/index.html.

National Park Service. “Fort George (U.S. National Park Service).” Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/places/fort-george.htm.

Parks Canada Agency. “Fort George National Historic Site of Canada.” Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=1236.

War of 1812.ca. “The Capture of Fort George, May 27th, 1813.” Accessed July 15, 2025. https://www.warof1812.ca/ftgeorge.htm.

- Note, the Amazon links to the published sources utilize my associates link. ↩︎