The Bear Flag Revolt and the Road to War

In the early summer of 1846, California stood at a geopolitical crossroads. While still nominally under Mexican control, the province had become a magnet for American settlers drawn by its fertile lands, coastal access, and strategic location. Tensions simmered as the United States and Mexico teetered on the edge of open conflict over disputed territory in Texas. When war officially broke out in May 1846, that tension spilled westward into California—transforming a regional standoff into a stage for imperial ambition.

httpsdigitallibraryusceduasset management2A3BF14YOV7WS=SearchResultsFlat=FP

Amid this charged atmosphere, a small group of American settlers in the Sonoma region launched what would become known as the Bear Flag Revolt. On June 14, they seized the Mexican garrison at Sonoma and declared the independent “California Republic,” raising a crude flag adorned with a lone star, a grizzly bear, and the words California Republic. General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo was the Commandante General of the Northern Frontier and oversaw the military garrison at Sonoma and managed vast land holdings in the region. Vallejo represented the official authority of the Mexican government. When the rebels seized Sonoma, they arrested Vallejo—along with his brother and others—not because of hostility toward him personally, but because capturing the senior Mexican official in the area would cripple local resistance and legitimize their nascent California Republic. Though the rebellion was short-lived—folding into U.S. military efforts just weeks later—it marked the beginning of the end for Mexican governance in California.

httpssachistorymuseumorg

The revolt was not an isolated uprising. It was deeply entangled with the larger theater of the U.S.–Mexican War (1846–1848), a conflict driven by expansionist zeal and framed by the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. As American naval forces moved to seize California’s coastal strongholds, the rebels’ actions provided both a pretext and a foothold. The Bear Flag Revolt thus became the spark that lit the fuse for California’s annexation.

As the newly declared California Republic took root, its leaders scrambled to defend their tenuous claim. What began as a symbolic uprising in Sonoma quickly turned into a campaign of skirmishes and reprisals. The rebels lacked supplies and formal organization, but their actions alarmed Mexican authorities, who moved to suppress the revolt before it could gain momentum. One of the first real tests of the Bear Flaggers’ resolve came just days after the republic was declared—at a quiet northern outpost called Rancho Olómpali. It was there, beneath the shadow of Mount Burdell and among the ancestral lands of the Coast Miwok, that California’s struggle for control turned violent.

Battle at Olompali

With the homemade Bear Flag flying over Sonoma, the Mexican government responded by sending a force under Captain Joaquín de la Torre northward from Monterey (California) to quell the rebellion. Tensions in the area escalated when two small parties of rebels including Thomas Cowie, George Fowler, William Todd, and others—set out from Sonoma to secure gunpowder and supplies from sympathetic Americans near Bodega Bay. The groups took different routes. Upon leaving Sonoma on June 16, William Todd and an “Englishman” companion embarked through the undulating vineyards of the Petaluma Valley, making their way toward coastal range and finally the sandy estuary of Bodega Bay. They secured their powder cache, but their return proved perilous: near Two Rock, they were seized by Padilla’s irregulars, who then held them at Rancho Olómpali—site of Ynitia’s adobe. Meanwhile, Thomas Cowie and George Fowler, dispatched on June 18 to Rancho Sotoyome, piled powder keg on mule back and set their course home. Their path through wooded ridges above Santa Rosa placed them on the same road as Californio patrols. The pair were captured by Mexican loyalists led by Captain Juan Padilla. The two men were killed and reportedly tortured before their deaths. The news of the killings enraged the Bear Flaggers and spurred a determination to confront those responsible.

In response, Lieutenant Henry L. Ford, an American settler in Sonoma who had been elected to command Company B of the militia (and given the rank of lieutenant) led a detachment of rebels from Sonoma, numbering no more than nineteen men. Ford aimed to intercept Padilla’s group and recover any other prisoners, particularly William Todd, who was still believed to be in captivity. Intelligence from local rancheros and scouting reports suggested that Padilla’s forces—and potentially the missing Americans—were camped at or near Rancho Olómpali, the estate of Coast Miwok leader Camilo Yñitia. Yñitia (sometimes spelled Inyatia) was the only Native Californian to receive—and successfully retain—a Mexican land grant in northern California during the Mexican period of control. His grant included more than 8,800 acres.

On June 24, 1846, Ford’s militia approached Rancho Olómpali expecting to find Todd and possibly avenge Cowie and Fowler. Instead, they stumbled upon a significantly larger force: Captain Joaquín de la Torre and his detachment of Mexican soldiers and irregulars, who had moved into the area in support of Padilla. The Mexican force was resting at Yñitia’s adobe home when the rebels arrived.

The two sides quickly engaged, exchanging fire across a pasture dotted with oak trees. Despite their numerical disadvantage, the rebels benefited greatly from superior weaponry. Armed with rifles, the rebels outranged the Mexican muskets, forcing de la Torre’s troops into defensive positions. The exchange of gunfire was intense but brief; one Mexican soldier was killed, another wounded, and eventually, the Mexican forces retreated south toward San Rafael.

During this skirmish, two American captives, including William Todd (Mary Todd Lincoln’s nephew), managed to escape and rejoin their fellow rebels.

The immediate aftermath of the Battle of Olómpali was significant. Although minor in scale, it emboldened the rebels and drew the attention of John C. Frémont and U.S. military forces. Shortly thereafter, Frémont consolidated control, effectively ending the Bear Flag Republic and facilitating the American annexation of California.

In the years following, Rancho Olómpali itself transitioned from a site of confrontation to one of preservation. Camilo Yñitia, who had maintained ownership of the land, eventually sold much of it in 1852. Today, the site of the battle is part of Olómpali State Historic Park, where visitors can walk the grounds and reflect upon a moment that helped shape California’s history.

American Viticultural Areas (AVAs)

An American Viticultural Area (AVA) is a legally defined wine grape-growing region in the United States, recognized by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB). AVAs are established based on distinct geographic, climatic, geologic, and cultural features that influence viticulture, such as soil type, elevation, weather patterns, and historical usage. Wineries may label their wine with an AVA name if at least 85% of the grapes used are grown within that AVA. The AVA system, first introduced in 1980, is designed to help consumers identify the origin and style of wines, similar to appellation systems in Europe.

While the site of the Battle of Olompali is outside an established AVA, Sonoma and the routes Thomas Cowie, George Fowler, William Todd, and Lt. Ford’s militia force took, literally crisscrossed multiple AVAs, highlighted below.

httpssonomacountyvintnersboxcoms4uiz97pwjzh5yjgxezq1m7ur4g3edgs4

Sonoma Valley

Terrain and Soil:

Sonoma Valley lies between the Mayacamas Mountains to the east and the Sonoma Mountains to the west, creating a protected corridor that retains warmth while allowing in marine fog from the south. The soils here are diverse: volcanic ash from ancient eruptions, gravelly alluvial fans, and clay-loam from sedimentary rock, offering excellent drainage and mineral content.

Primary Grapes Grown:

- Whites: Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc

- Reds: Zinfandel, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot

Wines Produced:

Sonoma Valley produces some of the most diverse and historically rooted wines in the state. Known for its warm days and cool nights, the valley supports both powerful reds and fresh whites. Zinfandel is a standout, with old vines producing rich, brambly wines full of blackberry, black pepper, and spice. Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot also perform well, especially in hillside vineyards, delivering full-bodied wines with firm tannins and deep fruit character. Chardonnay here is broader and riper than on the coast, often showcasing stone fruit, honeyed citrus, and a round, creamy texture. Sauvignon Blanc, with its crisp acidity and citrusy brightness, is gaining ground as well. With its mix of microclimates and soils, Sonoma Valley offers a well-rounded portfolio that reflects both heritage and innovation in California wine.

Historical Roots:

Sonoma Valley is the cradle of California winemaking. The first vineyards were planted by Franciscan missionaries at Mission San Francisco Solano in 1823 using Mission grapes. In 1857, Agoston Haraszthy founded Buena Vista Winery, introducing European varietals and techniques, and is often called the “Father of California Viticulture.” The valley saw substantial vineyard growth through the late 1800s, but like much of the state, it suffered setbacks during Prohibition. A postwar revival in the 1940s–70s brought prestige back to the region, helping define Sonoma’s reputation for high-quality wines.

Established as an AVA in 1981.

Los Carneros

Terrain and Soil:

Straddling the southern ends of Sonoma and Napa counties, Los Carneros is shaped by cool breezes off San Pablo Bay. The region is relatively flat with gentle rolling hills, underlain by dense clay and shallow loam soils that limit vine vigor and promote grape concentration.

Primary Grapes Grown:

- Whites: Chardonnay

- Reds: Pinot Noir

Wines Produced:

Los Carneros is one of California’s premier regions for sparkling wine and Burgundian varietals. Thanks to steady bay breezes and shallow clay soils, grapes retain natural acidity—ideal for méthode traditionnelle sparkling wines. These sparkling cuvées are crisp and refined, often blending Chardonnay and Pinot Noir for a bright citrus and green apple profile with hints of brioche and almond. Still wines from Carneros are equally outstanding. Chardonnay here is often zesty and mineral-driven, with lemon zest, white peach, and restrained oak. Pinot Noir tends to be light to medium-bodied, showing red berry fruit, dried rose, and savory herbal notes.

Historical Roots:

Los Carneros, meaning “the rams” in Spanish, has a grape-growing history that dates back to the 1830s under Mexican land grants. The region’s cool climate made it attractive for early farming and eventually for grape cultivation. In the 1970s, vintners rediscovered Carneros for its suitability to Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, especially for sparkling wines. Over time, still wine production expanded and the area became home to major sparkling producers as well as artisanal estates. Its location spanning Napa and Sonoma counties adds to its distinctiveness.

Established as an AVA in 1983.

Petaluma Gap

Terrain and Soil:

The Petaluma Gap AVA is defined by a unique wind corridor that pulls fog and cool ocean air through a break in the coastal mountains, making it extremely windy. Elevations range from 100 to 800 feet, with soils that include volcanic clay loam, gravelly sandstone, and uplifted marine sediment. Established as an AVA in 2018.

Primary Grapes Grown:

- Whites: Chardonnay

- Reds: Pinot Noir, Syrah

Wines Produced:

The signature here is Pinot Noir—dense in color and deeply aromatic, often showing layers of dark cherry, cranberry, clove, and forest spice. These wines benefit from the AVA’s strong marine winds, which slow grape development and enhance structure. Syrah also thrives here, taking on a cool-climate character that’s savory, peppery, and elegant, with notes of violet, plum, and smoked meat. Chardonnay from the Petaluma Gap tends to be leaner and more citrus-driven than in warmer parts of Sonoma, marked by bright acidity and a mineral finish.

Historical Roots:

Though ranching dominated the area historically, serious grape cultivation in the Petaluma Gap began in the 1990s. Pioneers recognized the region’s unique marine wind corridor, which slows ripening and helps develop complex flavors in grapes like Pinot Noir and Syrah. The long growing season and natural wind gap through the coastal hills. Wines from this area quickly gained acclaim, and a grassroots campaign led to official recognition. Established as an AVA in 2017.

Russian River Valley

Terrain and Soil:

The Russian River Valley is shaped by its namesake river and the heavy maritime fog that creeps inland through the Petaluma Gap. The region features rolling hills and flatlands with Goldridge sandy loam soils—well-draining, fertile, and ideal for Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

Primary Grapes Grown:

- Whites: Chardonnay

- Reds: Pinot Noir, Zinfandel

Wines Produced:

Morning fog from the Pacific, preserves acidity and lengthens the growing season. This results in Pinot Noirs that are plush and expressive, with notes of ripe cherry, cola, rose petal, and baking spice. The mouthfeel is often silky and balanced, making these wines both food-friendly and age-worthy. Russian River Chardonnays tend to be rich yet focused, often featuring ripe apple, pear, lemon curd, and a touch of toasty oak or creaminess from malolactic fermentation. The AVA also produces outstanding Zinfandel—jammy, spicy, and bold—and Gewürztraminer, which thrives in cooler pockets and delivers floral, aromatic white wines with a touch of sweetness or spice.

Historical Roots:

Viticulture in the Russian River Valley began in the 1800s, largely due to Italian immigrants who planted Zinfandel and field blends. The region’s Goldridge soils and foggy microclimate later proved ideal for cool-climate varieties. After a lull during Prohibition and the mid-20th century shift to orchards, the 1970s brought renewed interest in wine. Pioneers like Joe Rochioli and Davis Bynum helped establish the area’s reputation for world-class Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

Established as an AVA in 1983.

Sonoma Coast

Terrain and Soil:

Stretching from the Pacific coastline inland to the western edges of Sonoma Valley, the Sonoma Coast AVA is cool, foggy, and rugged. Vineyards are often perched on ridgelines above the fog line, with marine sediment soils, fractured sandstone, and gravelly loam. The terrain includes dramatic slopes, forested ridges, and coastal valleys.

Primary Grapes Grown:

- Whites: Chardonnay

- Reds: Pinot Noir

Wines Produced:

The Sonoma Coast wines are shaped by the region’s cool maritime climate and dramatic coastal terrain. Pinot Noir grows extremely well here, and trends toward earthy and complex, with flavors of wild berries, forest floor, and spice. These wines are known for their freshness and age-worthiness, thanks to natural acidity and a restrained fruit profile. Chardonnay from the Sonoma Coast leans toward the Burgundian style—mineral-driven, with citrus and green apple notes, often layered with subtle oak and saline undertones. The extended ripening period afforded by fog and cool breezes lends structure and finesse.

Historical Roots:

The Sonoma Coast was one of the last frontiers for grape growing in Sonoma County due to its rugged topography, fog, and remote location. Traditional agriculture focused on timber and dairy until the 1980s, when vintners began planting vines along ridgetops and coastal hillsides. The fog-cooled climate and complex marine soils proved ideal for Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. With growing recognition of its unique terroir, the region quickly gained status for elegant, age-worthy wines. Established as an AVA in 1987.

Weapon Spotlight: M1841 (the “Mississippi Rifle”)

httpswwwsieduobjectus model 1841 rifle3Anmah 417407

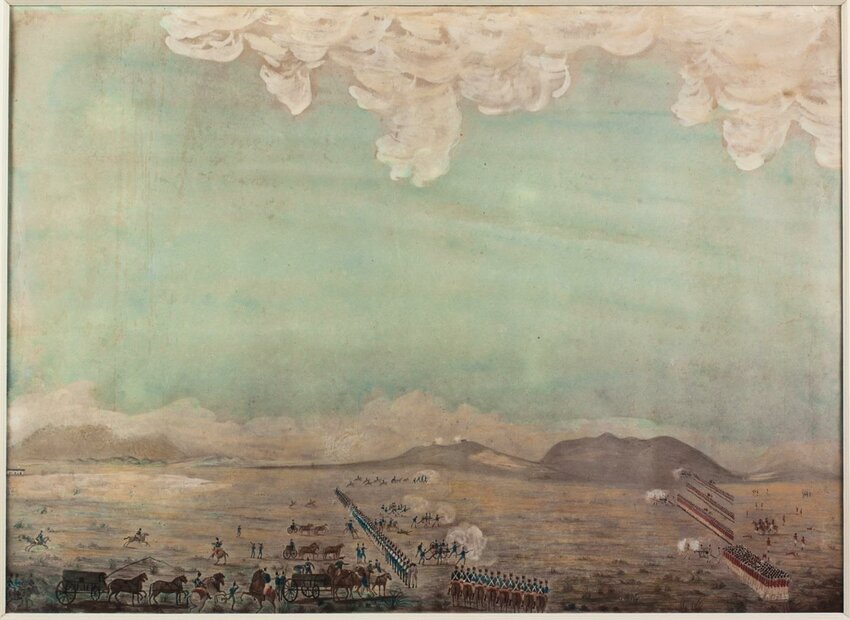

Though small in scale, the clash between Californio forces and American rebels at Olompali was shaped as much by terrain and politics as by the weapons each side carried. And among those weapons, the Model 1841 Rifle—a new and remarkably accurate firearm—may have played a quiet but decisive role.

Some firsthand accounts from the Olómpali skirmish suggest that the American side had rifles with far superior range to the smoothbore muskets used by the Californios. One observer noted that the enemy “could not shoot as far as the rifles used by some of the Bears.” While it’s impossible to know precisely what arms each volunteer carried, the description fits the M1841 rifle, which had only recently entered U.S. military service.

Developed at Harpers Ferry Armory and first issued in the early 1840s, the M1841 was a .54-caliber percussion rifle with a 33-inch rifled barrel and no bayonet lug. Unlike the standard-issue smoothbores, it was built for accuracy. It was also the first U.S. military rifle designed with interchangeable parts—a major advancement in arms production. Lightweight for its time and far more reliable than flintlock firearms, it was well-suited for scouts, skirmishers, and frontier volunteers.

httpswwwsieduobjectus model 1841 rifle3Anmah 417407

At the time of Olómpali, this new rifle was still largely unknown to the public. Its battlefield reputation came later—especially after the Battle of Buena Vista in 1847, where Mississippi volunteers under Jefferson Davis used it with devastating effect against Mexican forces. After that campaign the weapon gained the nickname “Mississippi Rifle.” But its presence—likely in small numbers—in California a year earlier demonstrates how quickly new military technology was spreading across the American frontier.

While the M1841’s .54-caliber round lacked the stopping power of later Minié ball rifles, its longer range, greater accuracy, and percussion ignition made it a formidable weapon in trained hands. Over the next decade, many were rebored to .58 caliber and retrofitted with bayonet lugs to keep pace with evolving tactics. Still, in 1846, it was cutting-edge.

At Rancho Olómpali, a few well-placed rifle shots may have changed the arc of the brief battle. More than that, they hinted at the future of American warfare—where precision, mass production, and new ignition systems would soon redefine the battlefield.