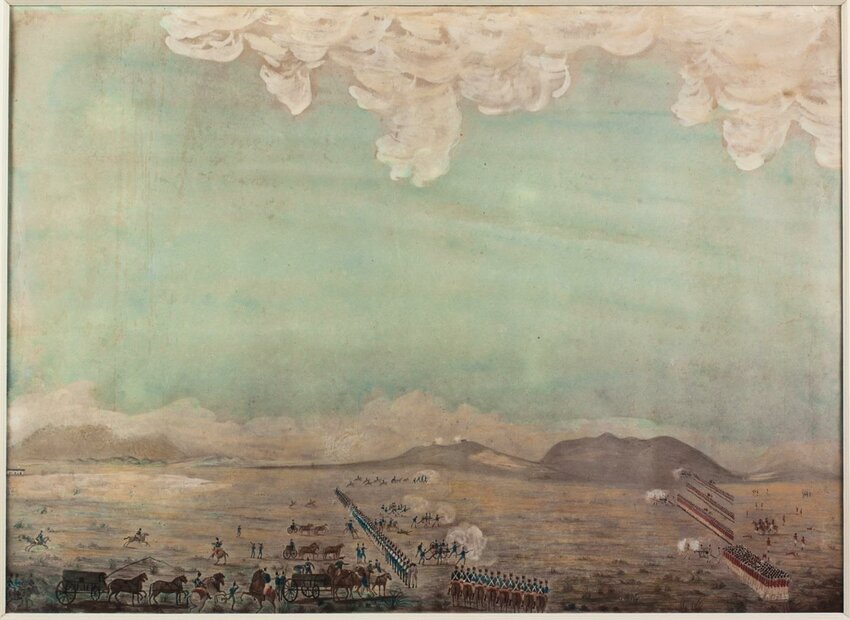

In the shadow of Normandy, another invasion unfolded in 1944—less heralded, but no less vital. Operation Dragoon, when allied infantry and tanks stormed the French Rivera in August of that year and rolled with the force of liberation through wine country and the Provençal hills, chasing the German 19th Army northward into retreat. This was the other D-Day, the southern stroke of a pincer meant to close around Nazi-occupied France. And it succeeded, with stunning speed.

Originally dubbed Anvil, the idea for a southern landing had long floated among Allied planners. American General George Marshall and President Franklin Roosevelt both saw the strategic logic: open a second front in France, secure deep-water ports like Marseille and Toulon, and accelerate the push into Germany. Joseph Stalin wanted it too. But Winston Churchill was skeptical, advocating instead for an assault through the Balkans. He worried that southern France would be a logistical distraction, drawing resources from Italy and diluting the drive toward Berlin. The idea was shelved more than once.

But by mid-1944, the congestion on Normandy beaches strained Allied supply lines. The ports of northern France could not handle the flood of men and matériel needed to sustain the liberation. So Dragoon was revived—not as an ideal operation, but a necessary one. Roosevelt overrode Churchill’s objections, and the operation was renamed and greenlit for August.

What unfolded was a model of Allied cooperation and military efficiency. The invasion force was formidable: the U.S. Seventh Army under Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch, including the 3rd, 36th, and 45th Infantry Divisions—battle-hardened in North Africa and Italy—would lead the assault. French Army B, commanded by General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, would follow, eager to reclaim native soil. Naval firepower under Vice Admiral Hewitt included battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and escort carriers. Air support was robust, with over 3,000 aircraft ready to provide cover and attack.

The German defenses were stretched thin. Army Group G, led by Field Marshal Johannes Blaskowitz, had too much ground to cover and too few capable troops to defend it. Worse, the French Resistance—coordinated under the umbrella of the FFI—was increasingly bold, sabotaging rail lines, ambushing convoys, and feeding intelligence to the Allies. Germany’s 11th Panzer Division was the only mobile reserve, and it was already under strain from months of war.

Before dawn on August 15, 1944, paratroopers and commandos struck first, clearing islands and landing zones around Le Muy to prevent German counterattacks. Then came the beach landings. U.S. forces came ashore along three sectors: Alpha Beach (near Cavalaire-sur-Mer), Delta Beach (near Sainte-Maxime), and Camel Beach (near Saint-Raphaël). Resistance varied; on Alpha and Delta, the landings were smooth—well-timed and well-supported by naval guns. Camel was a different story. Rough terrain and well-positioned enemy guns made progress difficult, but American troops pushed through, securing the area by nightfall.

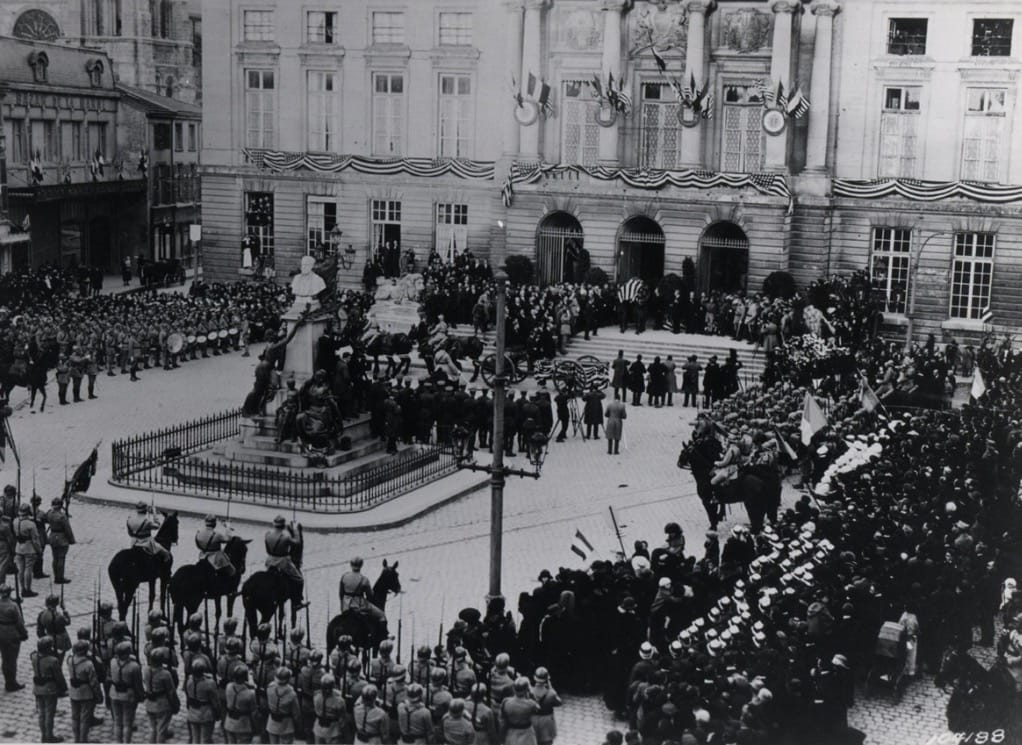

Within days, the Allies were advancing inland. The German defense collapsed more rapidly than expected. The real prize came quickly: the liberation of Toulon and Marseille. French forces, many of them colonial troops from North Africa, fought with determination to reclaim these historic cities. Street fighting was intense, and German troops fought hard, particularly in Toulon’s naval yards and Marseille’s maze-like Old Port. But within two weeks—by the end of August—both cities were in Allied hands. More than 25,000 German troops surrendered.

From the beaches, the allies drove north like a tidal surge. American armored columns raced into the Rhône Valley, aiming to cut off retreating German forces near Montélimar. The battle that followed there was fierce and chaotic. Allied units briefly controlled the heights and ambushed German convoys, but fuel shortages and the 11th Panzer Division’s desperate defense allowed many Germans to escape. Even so, the pressure was relentless. Lyon fell in early September. Resistance fighters rose up behind German lines, liberating towns before Allied tanks arrived.

By mid-September, Patch’s Seventh Army linkup with Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army near Dijon stitched the French front into a single continuous line—from the Swiss border to the Channel. The campaign in southern France had taken just four weeks. The cost was relatively light, the gains immense.

Dragoon was not without controversy. Churchill never forgave the decision to abandon the Balkans strategy. He believed that allowing the Soviets to advance unopposed into Eastern Europe would shape the postwar world in dangerous ways. But for the Allies on the ground, Dragoon was a triumph. The captured ports of Marseille and Toulon became logistical lifelines; by October, Marseille alone was handling a third of all Allied cargo in France. And for the people of Provence—many of whom had spent years under occupation—the American arrival felt like deliverance. Liberation moved not just in armored columns but through the vineyards and towns that had survived the long darkness. Resistance fighters laid down arms. Families raised French flags. The harvest, late that summer, was the first in years picked without fear.

Operation Dragoon may be less famous than its northern twin, but it reshaped the war in France. It was fast, effective, and deeply symbolic. It proved that the war would not be won solely on the beaches of Normandy but in every corner of occupied Europe—sometimes among the olive groves and vines of the south, where soldiers traded rations for bottles and freedom rode in on waves from the Mediterranean.

French Wine Regions

France’s wine regions are among the most strictly regulated in the world, governed by the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) system—now largely harmonized with the broader European Union Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) system. Under this structure, wine is classified not just by grape variety, but by terroir—a combination of geography, geology, climate, and tradition.

Each region is divided into appellations, which can be hierarchical:

- Regional appellations (e.g., Côtes du Rhône) cover broad areas.

- Subregional and village-level appellations (e.g., Côtes du Rhône Villages or Gigondas) are more specific and regulated.

- Cru-level designations (e.g., Châteauneuf-du-Pape) often represent the pinnacle of regional identity and quality.

French wine regions are tied to historical provinces and landscapes—Bordeaux to the Atlantic, Burgundy to central France, Champagne to the north, Alsace to the German border, and Provence and the Rhône to the south. Operation Dragoon cut through several of these southern regions, from coastal Provence into the southern Rhône and Languedoc.

Southern France: Vineyards of the Dragoon Corridor

Terrain and Soil:

The Allied advance during Operation Dragoon began along the sun-splashed Mediterranean coast and surged north through Provence, the southern Rhône Valley, and into the western Languedoc. These regions—steeped in viticultural history since Greek and Roman antiquity—offer a dramatic mix of terrain. Coastal Provence blends limestone hills and maritime plains with the rugged massifs inland, such as the Maures and Sainte-Baume. The Rhône corridor cuts through the vallée du Rhône méridionale, a patchwork of river terraces, stony plateaus, and gravel-rich alluvial fans. Further west, the Languedoc opens into a wind-swept expanse of garrigue-covered slopes and clay-limestone ridges. The Mistral winds in the Rhône and sea breezes along the coast moderate summer heat, reducing disease pressure and concentrating flavors in the grapes.

Grapes Grown:

Whites: Clairette, Grenache Blanc, Bourboulenc, Rolle (Vermentino), Roussanne, Marsanne

Reds: Grenache, Syrah, Mourvèdre, Carignan, Cinsault

Wines Produced:

- Côtes de Provence AOC: Pale rosés and aromatic whites dominate, with reds playing a supporting role. Found near the initial Dragoon landings between Toulon and Fréjus.

- Bandol AOC: Rich, age-worthy reds built on Mourvèdre, structured and spicy, from steep vineyards west of the landing zones.

- Coteaux Varois and Coteaux d’Aix-en-Provence: Inland appellations producing expressive rosés and earthy reds that mirror the surrounding scrubland and limestone terrain.

- Ventoux and Luberon AOCs: Found near the Allied push northward, these cooler, higher-elevation areas make fresh reds and floral whites.

- Côtes du Rhône and Côtes du Rhône Villages: Classic southern Rhône wines—generous, spicy blends led by Grenache—defined the vineyards along the Rhône corridor as U.S. troops raced north through Orange and Montélimar.

- Costières de Nîmes and Languedoc AOCs: At the western edge of the Dragoon advance, these sun-drenched zones yield bold reds and fresh whites with saline touches from nearby coastal wetlands.

Historical Roots:

Viticulture in Provence and the southern Rhône predates Rome, with Phoenician settlers planting vines around Massalia (modern Marseille) by 600 BCE. Roman expansion formalized viticulture along the Via Domitia, establishing the Rhône Valley as a crucial wine route. Monastic orders preserved winemaking during the medieval era, while papal influence at Avignon in the 14th century bolstered the Rhône’s prestige. By the 19th century, the Languedoc had become France’s volume-driven “wine lake,” while Provence retained its rustic charm and distinct rosé identity. Today, these regions reflect centuries of adaptation to terrain, war, and trade—making them both culturally and historically significant in the context of Operation Dragoon.

Weapon Spotlight: The M4 Sherman – Steel Through the Vineyards of Southern France

When you imagine the Southern France, the beaches of Provence, the golden hills of vineyards, and the fortified towns of Toulon and Marseille come to mind. Amidst this scenic landscape, in August 1944, a mechanical giant rumbled through the vineyards and olive groves: the M4 Sherman tank, the backbone of U.S. armored forces during Operation Dragoon.

The Birth of the Sherman

The M4 Sherman was conceived in 1941, born from the U.S. Army’s need for a reliable, mass-producible medium tank capable of meeting the mechanized warfare challenges of World War II. While not directly based on any single tank, its design borrowed lessons from the earlier M3 Lee/Grant, including engine layout and suspension. Chief Engineer James E. Allison and the Ordnance Department focused on three main goals: balance between armor and firepower, speed of production, and mechanical reliability in the field.

The Sherman was a symbol of American industrial power, with over 50,000 units produced during the war. Its versatility and adaptability made it indispensable on multiple fronts, from the beaches of Normandy to the sun-soaked vineyards of Provence.

Armor and Armament

The Sherman’s design evolved throughout the war to meet the growing threat of German armor:

- Armor: Early Shermans had up to 75 mm frontal armor, with thinner sides of 38–50 mm. Later models like the M4A3E8 “Easy Eight” featured sloped armor for better deflection and added protection.

- Main Gun: Initially armed with a 75 mm M3 L/40 gun, capable of tackling medium German tanks and fortified positions. Later models upgraded to 76 mm guns, and some variants carried 105 mm howitzers for infantry support.

- Secondary Weapons: .30 caliber Browning machine guns coaxially mounted with the main gun, hull-mounted .30s, and a .50 caliber Browning M2 on the turret provided anti-aircraft and anti-infantry defense.

This combination made the Sherman a flexible, reliable tool for both open-field assaults and urban combat in towns nestled among the vineyards.

Pros and Cons of the Sherman

Pros:

- Mechanical Reliability: Rarely broke down, even in rough terrain.

- Mobility: Top speeds of 24–30 mph, crucial for rapid inland pushes from beachheads.

- Ease of Maintenance: Designed for field servicing with minimal specialized tools.

- Production Scale: Mass-produced, ensuring overwhelming numbers against German forces.

Cons:

- Armor Weakness: Vulnerable to late-war German tanks like the Tiger and Panther.

- Limited Firepower: The 75 mm gun struggled against heavy armor unless flanking shots were possible.

- High Profile: Taller than many German tanks, making it easier to spot.

- Crew Space: Cramped interiors caused fatigue during prolonged operations.

Despite its limitations, the Sherman’s speed, reliability, and versatility made it an effective weapon in Operation Dragoon.

Influence on Later Tank Designs

The Sherman left a lasting legacy in armored warfare:

- M26 Pershing: Built on lessons from the Sherman’s limitations in armor and firepower.

- M47 and M48 Patton Tanks: Incorporated mobility, firepower, and production scalability lessons.

- Global Impact: Many nations adopted or upgraded Shermans after the war, making it a staple of postwar armored doctrine.

Even today, the Sherman stands as a symbol of American adaptability and mass-produced strength, rolling across vineyards and battlefields alike.