Selecting America’s World War I Unknown

On the morning of October 24, 1921, a U.S. Army sergeant walked into the Hôtel de Ville—the city hall—of Châlons-sur-Marne (today Châlons-en-Champagne), France. Before him rested four identical flag-draped caskets, each containing the remains of an unidentified American soldier who had fallen in the Great War. Carrying a spray of white roses, the sergeant slowly circled the caskets, paused, and placed the flowers on one. That simple act determined which Unknown Soldier would be brought home to represent all Americans who made the ultimate sacrifice for their nation, losing both their lives and their identities.

Why an “Unknown”?

World War I was the first truly global industrial war. Artillery, machine guns, and high-explosive shells disfigured the landscape and the men who fought across it. Entire units vanished in bombardments so fierce that many soldiers could not be identified afterward. For grieving families, there was often no body to bury and no grave to visit.

Allied artillery guns fire on German positions along

the Western Front National Archives and Records AdministrationNARA

Ruins of a church in Montfaucon

France NARA

To meet this universal grief, nations created memorial tombs dedicated to an unidentified soldier who would symbolize all the missing. Britain interred its Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey on November 11, 1920. France followed the same day, placing its Soldat Inconnu beneath the Arc de Triomphe in Paris.

Moved by these tributes, the U.S. Congress passed legislation on March 4, 1921 authorizing a similar ceremony. Arlington National Cemetery, already a national military shrine, was chosen as the site. The intent was both simple and profound: to give America’s bereaved a place of collective mourning and to ensure that even the nameless dead would be remembered with honor.

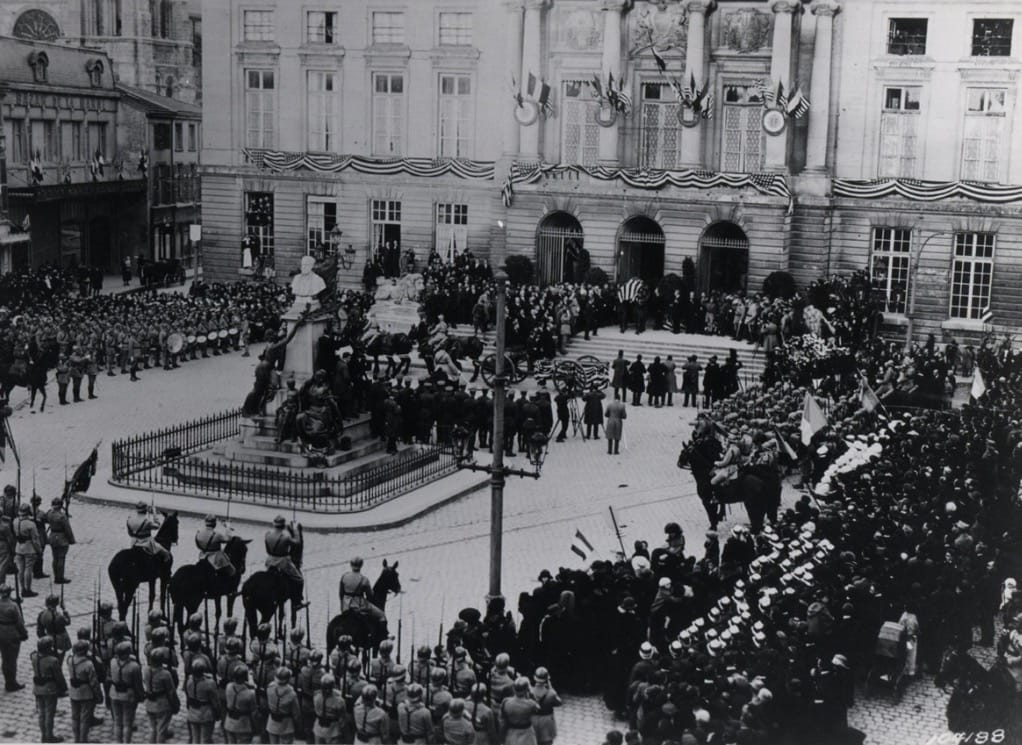

Ceremony in Châlons

To preserve complete anonymity, the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps selected one unidentified set of remains from each of four American military cemeteries representing the major campaigns in France—Aisne-Marne, Meuse-Argonne, Somme, and St. Mihiel. These four caskets were taken to Châlons-sur-Marne, a market city near the Marne River whose streets had seen combat only three years earlier.

The city’s Hôtel de Ville (City Hall) was chosen for the selection because it provided a solemn civic setting close to the battlefields where thousands of Americans had fought and died. On October 24, 1921, the building became, briefly, the symbolic crossroads of memory for both France and the United States.ty hall on October 24.

The Soldier and the Roses

The task of choosing fell to Sergeant Edward F. Younger, a decorated infantry veteran then serving with the American forces occupying Germany. He was instructed to enter the hall alone, walk among the four identical caskets, and select one without guidance or information.

Younger carried a spray of white roses provided by a local Frenchman, Brasseur Brulfer, a former member of the Châlons city council who had lost two sons in the war—one whose body was never identified. As Arlington National Cemetery historians note, Brulfer’s gift gave the moment deeper resonance, linking France’s mourning to America’s.

After walking around the caskets several times, Younger stopped before one, bowed his head in silence, and laid the roses upon it. The choice was final. The three unselected Unknowns were reburied together at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery, where they remain as silent witnesses to the Unknown’s universal meaning.

A funeral city in Champagne country

Châlons-sur-Marne lies in the Champagne plain of northeastern France—a landscape of gentle hills and chalky soils famous for vineyards, not warfare. Yet from 1914 to 1918, this peaceful region became a corridor of devastation. German armies twice advanced toward Paris along the Marne River, and Allied counterattacks turned its fields into killing grounds.

By holding the selection in Châlons, American and French officials placed the ceremony in the very landscape that had swallowed so many soldiers. The people of Châlons knew loss firsthand: their homes were shelled, their families displaced, and their sons killed or missing. For the residents, the presence of American soldiers choosing an Unknown among their ruins brought the promise that sacrifice would not be forgotten.

For modern visitors, Châlons represents both worlds of Champagne—the vineyards that yield celebration, and the soil that absorbed the war’s dead.Châlons-sur-Marne (Châlons-en-Champagne) sits in the Champagne plain, a region whose vineyards and small towns were battered by the war’s tides. The choice of this city—within marching distance of the Marne battlefields—placed the ceremony amid the very landscape Americans had fought to hold in 1918. For Vini Bellum readers, that geography matters: the Unknown was selected not in a distant office but in a market-and-wine town whose people had lived through the same artillery shelling and devastation that made so many soldiers unidentifiable.

The voyage home aboard USS Olympia

After a dignified procession through Paris, the chosen casket was carried to Le Havre, where the U.S. Navy took charge. The armored cruiser USS Olympia, famed as Admiral George Dewey’s flagship at the 1898 Battle of Manila Bay, was selected to bear the Unknown home.

The ship departed Le Havre on October 25, 1921, with a Marine honor guard standing watch day and night. Navy and museum records describe the Atlantic crossing as storm-tossed and dangerous. The guard lashed the casket and themselves to the deck to prevent movement as waves crashed over the bow. After nearly two weeks at sea, Olympia entered the Washington Navy Yard on November 9, 1921, greeted by salutes and silence.

That same ship, preserved today at the Independence Seaport Museum in Philadelphia, remains a tangible link to the Unknown’s journey.

Bibliothèque nationale de France

A people’s funeral

From November 9–10, the casket lay in state in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda, where an estimated 90,000 mourners filed past to pay their respects. On Armistice Day, November 11, a solemn procession crossed the Potomac River to Arlington National Cemetery’s Memorial Amphitheater.

There, before thousands of spectators and global dignitaries, President Warren G. Harding awarded the Medal of Honor to the Unknown on behalf of the American people, while Allied nations bestowed their own highest decorations. The white roses from France appeared again in photographs and floral displays throughout the ceremony, symbolizing continuity between the fields of Champagne and the hills of Virginia.

When the bugler sounded “Taps,” the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was sealed, completing a journey from anonymity to immortality.

Why Châlons still matters to us today

More than a century later, the Hôtel de Ville at Châlons-en-Champagne still houses the small, echoing room where Sgt. Younger made his silent choice. There are no speeches, no grand architecture—just the memory of a man and four coffins.

The ceremony’s enduring power lies in its restraint and humanity. It spoke for a generation that had seen mechanized slaughter on an unimaginable scale and longed for dignity amid loss. For Americans today, especially those who have walked the vineyards of Champagne or the quiet rows of the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery, the story unites two landscapes: one where the Unknown fell, and one where he rests in honored glory beneath the white marble Tomb at Arlington National Cemetery.

Champagne around Châlons-en-Champagne

Terrain & Soil

Châlons-en-Champagne sits in France’s Marne department, within the broader Champagne AOC. The area is part of the Paris Basin, where ancient seas left thick layers of limestone and chalk (Cretaceous chalk in particular). This chalk matters for the vines: it drains quickly (so roots don’t sit in water), holds just enough moisture for dry summers, and acts like a thermal battery, absorbing heat by day and slowly releasing it at night. Those traits help grapes ripen in Champagne’s cool, northern climate. The same geology created vast underground chalk cellars (crayères) with naturally cool, stable conditions are ideal for aging sparkling wine. In 2015, UNESCO added the “Champagne Hillsides, Houses and Cellars” to the World Heritage List, recognizing this unique mix of land, artisan wine production, and subterranean architecture.

Grapes Grown

Champagne allows seven grape varieties by rule, but three dominate almost all plantings and blends:

- Chardonnay (white): brings citrus, floral notes, and a mineral line—often grown where chalk lies close to the surface.

- Pinot Noir (black): adds structure, body, and red-fruit tones.

- Meunier (black): offers supple fruit and resilience in cooler or clay-influenced sites.

The four traditional minor grapes—Arbane, Petit Meslier, Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris—are still permitted but planted in smaller quantities today.

Wines Produced

The flagship wine is Champagne, a sparkling wine made by a second fermentation in the bottle (the “traditional method”). After fermentation and bottling, wines age on their lees (yeast sediment), which deepens flavor and texture. By regulation, non-vintage Champagne must age at least 15 months before release (with 12+ months on lees), and vintage Champagne must age at least 36 months—minimums many producers exceed for complexity. The region also produces still wines under the Coteaux Champenois AOC, but are comparatively small in production. Châlons itself is home to historic house Joseph Perrier (founded 1825), a useful touchpoint for visitors exploring local cellars and seeing how base wines from different villages are blended and then aged in chalk caves.

Historical Roots of the Wine Region

For centuries this northern frontier of French viticulture made mostly still wines. Between the 17th and 19th centuries, improvements in glass strength, cork quality, and cellar practice allowed producers to refine bottle fermentation and handling, turning Champagne into the world’s emblematic sparkling wine. In the 20th century, the region formalized protections: AOC “Champagne” status (decreed 1936) and creation of the interprofessional body now called the Comité Champagne (CIVC) (1941), which codifies standards and defends the appellation. The UNESCO inscription in 2015 highlights how vineyards, grand “houses,” and chalk cellars together form a cultural landscape built around sparkling wine, one that even sheltered civilians in the crayères during World War I, showing how geology, community, and winegrowing have been intertwined here.

Commemoration in the Heart of Champagne

Unlike most Vini Bellum stories, this is not about a battle fought through vineyards or a campaign waged across rolling hills. It is about what came after, the silence, the search for meaning, and commemorating all who never returned. The selection of America’s Unknown Soldier did not happen in Washington or Paris, but in Châlons-sur-Marne, in the very heart of France’s Champagne country, where in 1921 the earth still bore the scars of war and the vines were just beginning to grow back.

That setting makes the story a perfect fit for Vini Bellum. The same chalk soil that anchors the vines of Champagne also cradled the dead of the Great War. Here, in a city known more for celebration than sorrow, a simple ceremony to choose an unknown has forever shaped America’s national memory.

The story of the World War I Unknown reminds us that remembrance is not confined to monuments or anniversaries. It endures in the landscapes where battles were fought, in the families who mourned, and in a ceremony that linked French and American grief. More than a century later, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier remains as vital to our national conscience as it was in 1921. It is an eternal pledge that America never forgets its defenders, known or unknown.