The Biga River runs quietly today through northwestern Turkey, its waters winding across the plain before spilling toward the Sea of Marmara. It’s a peaceful place with olive groves and vineyards scattered among rolling hills, but 2,300 years ago these fields echoed with the thunder of battle. Here, on the banks of what the ancients called the Granicus, a young Macedonian king crossed from ambition into immortality.

Crossing Into Asia

In the spring of 334 BCE, Alexander III of Macedon, twenty years old and newly crowned as King, stood on the edge of Asia. Behind him lay Greece, still wary of his father’s empire; ahead stretched the vast Persian dominion of Darius III. His father, Philip II, had dreamed of avenging the Persian invasions that had once burned Athens. Alexander took that unfinished dream and made it his own.

He had already proven himself in battle at home, crushing rebellions and securing his northern borders. Now he aimed east—not just for vengeance, but for destiny. With thirty thousand infantry and five thousand cavalry, he crossed the Hellespont and marched along the coast of Asia Minor, carrying with him the faith that the world could be remade under his command.

The River and the Enemy

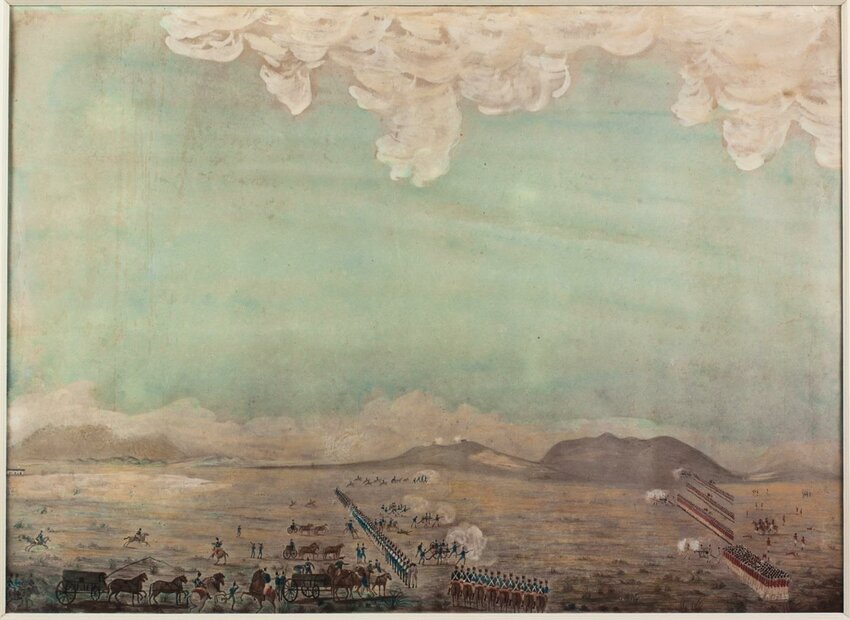

The Persian satraps of Asia Minor gathered their armies near the Granicus (today Biga) River, a swift, shallow stream flowing through open plain beneath low ridges. They expected Alexander to hesitate before forcing a crossing under fire. Instead, he spurred his horse into the current and charged.

The Persians held the high bank, their cavalry and Greek mercenaries arrayed in glittering ranks. The first Macedonians who tried to climb the opposite shore were cut down. But Alexander pressed forward, speartip flashing, his Companions forming around him in the chaos of the ford. In that violent tangle of horses and men, he was struck on the helmet by a Persian noble’s sword. He survived, killed his attacker, and led another assault up the bank. By the day’s end, the Persian cavalry broke. The mercenary infantry, abandoned by their commanders, was surrounded and destroyed.

When it was over, the river ran red, and the Persian defense of Asia Minor was shattered.

Finding the Field

For centuries, the exact location of the battle eluded historians. Ancient texts spoke of the Granicus, but the course of rivers shifts and memories fade. Recently, archaeologists led by Dr. Reyhan Körpe of Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University have identified what they believe is the true battlefield on the Biga Plain, near the modern town of Biga in Turkey’s Çanakkale Province.

The landscape matches the old accounts: a river cutting through open ground beneath a gentle rise, where the Persian infantry could have formed their line. Excavations have uncovered burial sites and artifacts consistent with a clash of armies. It’s an unassuming countryside today, but one where the earth still whispers of bronze, iron, and glory.

The Birth of “the Great”

The victory at the Granicus did more than open the gates of Asia Minor. It proved that Alexander’s audacity could conquer empires. Within months, cities along the coast surrendered; within years, he would stand at Persepolis, master of the Persian world. But it was here, beside this quiet river, that he first earned the title the world remembers.

He crossed a stream and emerged as Alexander the Great.

On the Soil of the Biga Plain

The vineyards that grow near Biga today trace their roots to the same fertile soil where Macedonian and Persian blood once mingled. The region lies within the greater Çanakkale wine zone of northwestern Turkey—an ancient terroir that produced wine even in antiquity. Karabiga, the small coastal town at the river’s mouth, was known to the Greeks as Priapos, famed for its wines.

It’s easy to imagine the scent of those same vines carried on the breeze that morning in 334 BCE, mingling with the river mist and the smell of warhorses. History, like wine, is born of soil and struggle. And in the valley of the Granicus, both took root.

Turkish Wine Regions: From West to East

Stretching across two continents and wrapped by four seas, Turkey holds some of the oldest wine-growing soils on earth. From the windswept cliffs of Thrace to the sunburned valleys of Anatolia, its vineyards trace the same routes once taken by armies, traders, and myth. Vines have grown here for millennia—long before the word “wine” ever crossed Greek or Latin tongues.

Modern Turkish viticulture organizes this ancient landscape into several broad regions, but geography still rules more than regulation. In the northwest, the Marmara and Thrace zone surrounds the Sea of Marmara, its vineyards cooled by sea breezes and tempered by the crossing of Europe and Asia. This is where Istanbul meets the Aegean, and where wine carries both maritime freshness and the weight of centuries.

Further south and west lies the Aegean, the heart of Turkish winemaking today. Here, the climate turns Mediterranean—dry summers, gentle winters—and the soils run stony and light. The vineyards near Izmir and along the Meander River valley give rise to many of the country’s best-known bottles, a blend of native and international varietals.

Inland, the air grows sharper. The Central Anatolian plateau sits high and dry, its winters fierce and its soils lean, demanding much of the vine but rewarding it with intensity and resilience. Farther east, beyond the volcanic ridges and steppe winds, viticulture becomes rarer but not absent as small pockets still nurture ancient vines.

Terrain & Soil

The Biga Plain and surrounding hills in Çanakkale Province lie close to the coast where the ancient river (Granicus) flows into the Sea of Marmara. The terrain is relatively gentle: a broad river valley and plain, backed by low ridges.

Viticulturally, the soil in the broader Marmara/Thrace wine zone (into which this area falls) is described as having limestone, gravelly loam and dense cracking clay.

Around Çanakkale, calcareous clay soils that retain moisture and soften strong-skinned grapes such as Boğazkere in that zone.

The climate influences are maritime-moderated: proximity to the Sea of Marmara and Aegean shores offers milder winters and cooling breezes in summer compared to the interior. This means vineyards here can extend down to lower altitudes and enjoy longer growing seasons than purely inland zones.

Grapes Grown

In the Çanakkale / Biga zone, vineyards cultivate a mix of indigenous Turkish grape-varieties and some international ones. Among the key indigenous varieties in the wider region:

- Karasakız (also known as Kuntra) is grown on nearby Bozcaada and the Thrace/Marmara coast.

- Boğazkere, though more often associated with Eastern Anatolia, shows up in calcareous clay soils of Çanakkale.

- Local vineyards around Gelibolu (Gallipoli) and Çanakkale using varieties like Kınalı Yapıncak and Karasakız.

- International varieties (Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc) are increasingly present across Turkey and in the Marmara/Thrace/Aegean coastal wine zones.

Wines Produced

Wines from this region reflect the interplay of indigenous character and maritime-coastal maturity. Typical profiles include:

- Red wines from Karasakız/Kuntra tend to be medium body, moderate tannins, fresh red fruit character — especially when grown on low-hills with sea breeze influence. More structured reds from Boğazkere (or blends with it) show up where soils retain moisture beneath hot summers, accentuating the bold skins and aging potential.

- Whites and rosés from coastal plots exploit the cooling breezes and moderate winters, yielding crisp, balanced wines with vitality.

Historical Roots

The viticultural heritage of the Biga/Çanakkale region is deep. The same lands that hosted the Battle of the Granicus in 334 BCE also lay in a geography long accustomed to grape-growing, from ancient Greek settlements through Roman and Byzantine eras, and into Ottoman times. The town of Karabiga (at the river’s mouth) was known in antiquity (as Priapos) for its wines.

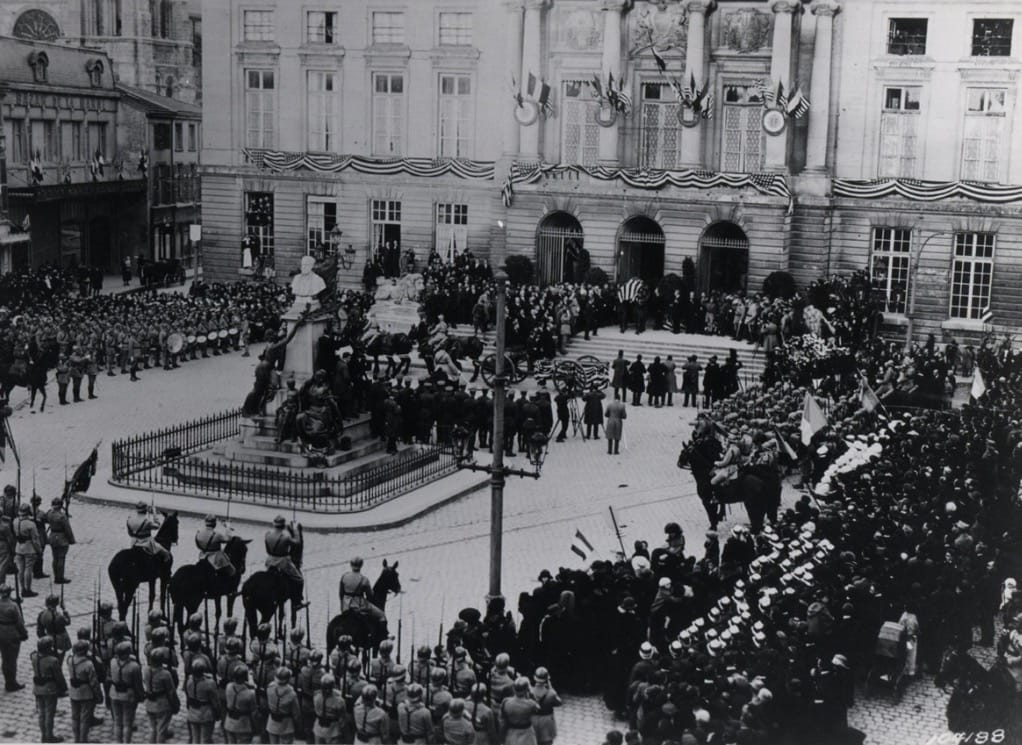

In modern times, the wine industry in Turkey took renewed impetus after mid-20th-century liberalization. Yet the western coastal zones such as Marmara, Thrace and Aegean (including Çanakkale) have taken a leading role in the emerging wine tourism and boutique-winery movements.

Unearthing the River of Legends

Recent archaeological work on the Biga Plain has begun to link the written history of the Granicus to the landscape itself. Excavations led by Dr. Reyhan Körpe of Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University have uncovered burial sites, artifacts, and terrain features consistent with ancient accounts of Alexander’s first major battle. The contours of the river valley, the elevated ground where Persian forces formed their line, and the open plain where Macedonian cavalry advanced now give tangible shape to a story that once lived only in chronicles.

Locating the actual ground of Alexander’s first major victory helps clarify both his early campaign and the wider geography of Persian control in Asia Minor. It situates the opening move of his empire-building within a landscape that remains vital today, a region where agriculture and winemaking still define daily life. The discovery of the battlefield does not change the known outcome, but it anchors the story of Alexander’s emergence as “the Great” in verifiable soil, allowing historians to connect written accounts with the enduring features of the land itself.