Prologue: Empire, Peninsula, and the Wine Country

In 1809, Europe was ablaze with the Napoleonic Wars. Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte had swept much of Europe into his orbit, but the Iberian Peninsula remained a stubborn liability: Spain, forced into alliance, soon rebelled; Portugal, a British ally, defied French domination. The peninsula thus became a grinding theater of liberation war, guerrilla struggle, and conventional campaigns—and it drained French strength at the margins of Napoleon’s grand design.

Napoleon hoped that by seizing Portugal, he could choke Britain’s access to continental trade, isolate British influence, and consolidate control over Iberia. From 1807 onward, French armies invaded Portugal (first under Junot, then subsequent attempts), only to be driven back.

By early 1809, the French high command—keen to reassert momentum—ordered Marshal Nicolas Soult to lead a fresh invasion via northern Portugal. His objectives: capture Porto (Portugal’s second city), establish a base, then push south toward Lisbon.

Facing him were Portuguese forces—steady but poorly equipped—and, crucially, a renewed British commitment under Arthur Wellesley (soon to be Duke of Wellington), who had arrived to coordinate allied resistance and eventually reclaim the country.

It is into this drama that Porto and its wine-river, the Douro, would serve not as backdrops but actors in the conflict.

Act I: The Storming of Porto (29 March 1809)

March into the Douro Valley

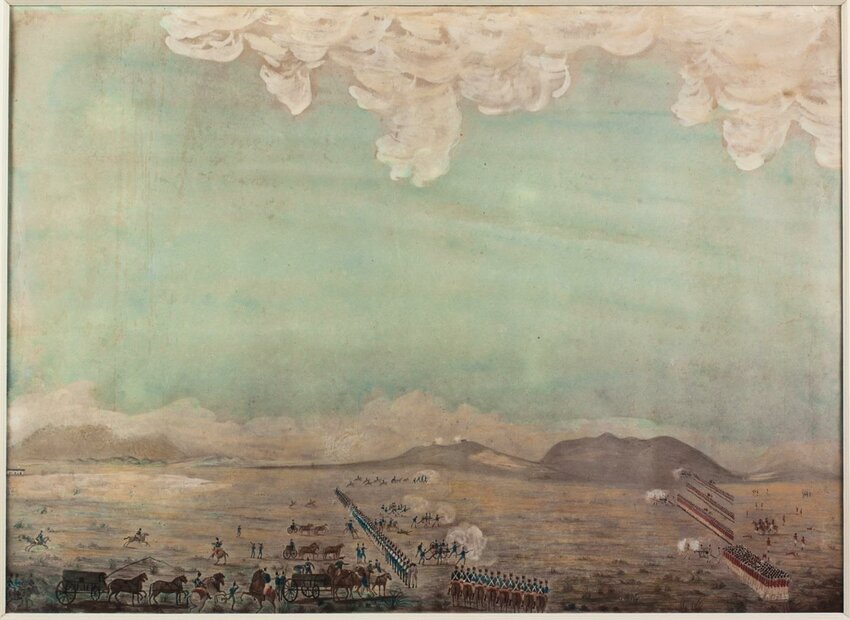

Soult’s corps—drawn from his II Corps divisions under Merle, Mermet, Heudelet, Delaborde—crossed from Galicia into northern Portugal. After taking the fortified border town of Chaves, he swung west toward Braga, smashing Portuguese militia and disorderly forces at Braga on 20 March.

Portuguese resistance crumbled before his veteran infantry. Meanwhile, communications and local insurgent bands began troubling French lines, but Soult pressed on, confident in his mission.

Clash at Porto’s Gates

By late March, Soult approached Porto from the north and east. The city’s defenses were ill-prepared: a motley force of regular troops, municipal militias, and citizen volunteers—many poorly armed—under General Parreiras and allied leaders sought to make a stand.

On 29 March, French columns attacked along the weakest sectors north of Porto. Portuguese lines buckled. Panic seized the defenders and civilians alike as the French surged toward the Ponte das Barcas (Bridge of Boats), a floating pontoon spanning the Douro.

Tragedy on the Bridge and City Fall

In the mass exodus, the bridge collapsed under the weight of crowds, horses, guns, and fleeing troops. Thousands drowned or were trampled. This Bridge-of-Boats disaster remains one of Portugal’s darkest wartime tragedies.

As French cavalry and infantry surged in, streets became battlegrounds. The defenders, scattered and leaderless, were routed. French forces sacked Porto, captured arms, stores, and merchant ships in the harbor, and secured the city as their foothold.

By nightfall, Porto lay in French hands—but without control of supply lines or local goodwill. Soult’s triumph was pyrrhic.

Interlude: Holding Porto Under Pressure

After capturing Porto, Soult consolidated his force, repaired logistics, and planned the next thrust toward Lisbon. But he faced relentless guerrilla action and Portuguese ordenanças (local militias) which severed his communications and strained supply lines.

Meanwhile, Wellesley, who had landed in Portugal earlier that year, reorganized British regiments and rallied Portuguese levies. He moved north to challenge Soult, linking with General Beresford, and began a swift campaign to relieve Porto and expel the French.

Algarve History Association

A prelude skirmish at Grijó (10–11 May) cleared the path toward Porto’s south bank, enabling Wellesley to position his army at Vila Nova de Gaia, facing Porto across the Douro.

For his part, Soult anticipated an assault across the river. He anticipated crossings, ordered all boats pulled to the north bank, dismantled floating bridges, and concentrated defenses along possible river approaches.

Act II: The Crossing of the Douro (12 May 1809)

Nightfall Strategy and the Seminary Target

On the evening of 11–12 May, the river lay quiet. Wellesley stationed his headquarters in the Serra do Pilar Monastery on the south bank, commanding a view across to Porto’s heights. Through telescopes, his staff spotted the Porto Diocesan Seminary perched on the north bank—a substantial, unfinished three-story structure with no visible garrison. It offered a tempting foothold if seized.

At about 2:00 a.m., an explosion rent silence: the pontoon bridge was blown up (likely by French demolition). Wellesley’s troops awakened and marched toward Vila Nova, massing behind Serra do Pilar’s heights.

Waters, the Barber, the Barges

Wellesley dispatched Colonel John Waters, who spoke Portuguese, upstream by skiff to seek hidden crossings. Guided by locals (notably a barber), Waters found a small skiff and, more crucially, four large, unguarded barges moored on the north bank. He ferried them back across the river unseen.

Under Wellesley’s orders, these barges were sailed back and forth to carry infantry across the Douro—one regiment at a time. The 3rd Regiment (the Buffs) was first loaded and landed quietly at or near the seminary. The British then secured the seminary walls, closed its north gate, and began fortifying the position.

French troops awoke to find British redcoats entrenched behind their lines. They launched counterattacks from Porto, notably against the seminary, but were repulsed, suffering heavy losses and failing to dislodge the defenders.

Cascade of Crossings and French Collapse

Simultaneously, Major-General John Murray had earlier crossed farther upstream at Avintes with ~2,900 men. His force marched inland to threaten French retreat along the eastward road out of Porto. Although Murray declined to press a full engagement, his positioning contributed to cutting off French escape routes.

Once entrenched at the seminary, Wellesley pressed the attack. The French, now encircled in Porto and facing a dawn offensive, broke. Soult ordered withdrawal toward the northeast, leaving behind guns, wounded, and stores. His columns streamed out in disorder over the hills.Soult’s beaten corps, stripped and starving, escaped over altitudes and trails, evading complete capture but never again recovered a foothold in northern Portugal.

Epilogue: Porto, Power, and the Peninsular Crucible

The twin battles fought at Porto in 1809 closed one chapter of Napoleon’s war in Portugal and opened another in the long unraveling of his empire. When Marshal Soult’s army retreated in disarray through the mountains of Galicia, the defeat did more than liberate a city—it shattered the illusion of French invincibility on the Iberian Peninsula. Napoleon’s grand strategy of sealing Britain off from continental trade through conquest of Portugal had failed once again, undone by the resilience of a small nation and the audacity of a British general who understood both terrain and timing.

Arthur Wellesley’s victory on the Douro propelled him to new prominence. Within months, he would march into Spain and fight alongside Spanish allies at Talavera, where he earned the title Viscount Wellington. Yet Porto remained his first great demonstration of mastery in the Peninsular War—a campaign that would bleed France for five long years, drain its armies, and contribute mightily to the collapse of Napoleon’s imperial dream.

But beyond its military consequences, Porto’s story is inseparable from its geography and its wine. The Douro River, lined with steep terraces and stone quays, shaped the very character of the battle. The rabelo boats, built to carry casks of Port from the inland vineyards to the lodges of Vila Nova de Gaia, became unlikely instruments of war when British troops used them to cross under fire. The same currents that had borne centuries of trade and prosperity now carried soldiers to victory.

From the monastery heights of Serra do Pilar, Wellesley’s telescopes swept the opposite bank to the walls of the seminary, a sturdy structure that would become the key to the operation. His decision to seize it with a handful of men—and his reliance on local guides who knew every bend of the river—showed how leadership and intelligence could turn landscape into weapon. In Porto, as in so many campaigns of the Peninsular War, the difference between defeat and triumph lay not in numbers, but in knowing how to read the ground beneath one’s feet.

The river that made Port famous thus also witnessed one of the most daring actions of the war. Where once barrels of wine drifted downstream, boats now ferried soldiers. And when the smoke cleared, the Douro flowed on—its waters carrying the echo of musket fire and the promise of a nation reclaimed.

Portuguese Wine Regions

Portugal’s vineyards are organized under a system similar to France’s AOC, known as Denominação de Origem Controlada (DOC)—part of the European Union’s Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) framework. The DOC defines wines by their geographic origin, grape varieties, and production methods, preserving centuries of regional identity. Beneath the DOCs are broader Vinho Regional (VR) designations—comparable to France’s IGP—which allow greater flexibility while still emphasizing regional character.

Hierarchy of Classification

- DOC (Denominação de Origem Controlada): The highest designation, defined by strict regulations on grape varieties, yields, and aging.

- Vinho Regional (VR): Regional wines that may use non-traditional blends but still originate within a delimited area.

- Vinho: The broadest category, often simple table wines without geographic indication.

Northern Portugal: Vineyards of the Douro and Vinho Verde

Terrain and Soil

The Douro Valley, among the oldest demarcated wine regions in the world (established 1756), stretches eastward from Porto through narrow canyons and terraced slopes carved by the Douro River. Schistous soils dominate, fractured to allow deep vine roots and heat retention that ripens grapes along this harsh interior. Near the river mouth, where the First and Second Battles of Porto took place, the land flattens into the coastal plain of Porto and Vila Nova de Gaia, where the river meets the Atlantic.

Here, barrels of fortified Port wine were historically aged in the cool cellars of Gaia after being shipped downriver in rabelo boats from the vineyards upstream. Just to the north lies Vinho Verde DOC, a lush, rain-fed region of granite soils producing crisp, low-alcohol wines—a marked contrast to the Douro’s arid terraces.

Grapes Grown

Douro DOC

- Reds: Touriga Nacional, Touriga Franca, Tinta Roriz (Tempranillo), Tinta Barroca, Tinto Cão

- Whites: Rabigato, Viosinho, Gouveio, Malvasia Fina

Vinho Verde DOC

- Whites: Alvarinho, Loureiro, Arinto (Pedernã)

- Reds: Vinhão, Borraçal, Espadeiro

Wines Produced

- Porto DOC (Fortified): Rich, sweet wines ranging from ruby to aged tawny styles, produced from Douro grapes but blended and matured in Vila Nova de Gaia’s lodges—the very quays beneath which British troops launched their daring river crossing in 1809.

- Douro DOC (Still Wines): Dry reds of power and minerality, increasingly prominent today, born from the same rugged slopes that once echoed with the movements of French and Anglo-Portuguese armies.

- Vinho Verde DOC: Light, effervescent whites that mirror the cool rains of Portugal’s northern hills, far removed in tone but not in proximity from the battle zone at Porto.

Historical Roots

Viticulture in northern Portugal predates Rome, though it was under Roman Lusitania that vineyard terraces expanded along the Douro. During medieval centuries, Cistercian monasteries refined the region’s viticulture, linking wine production to monastic trade networks. By the 17th and 18th centuries, Port wine—fortified for export to Britain—dominated the economy of Porto and Vila Nova de Gaia, making the Douro a lifeline of Anglo-Portuguese commerce.

When war arrived in 1809, it did so across a landscape long entwined with British trade. The same river that carried casks to English merchants now bore British soldiers against Napoleon’s occupying troops. The Douro crossings, like the wines born of its banks, were a fusion of daring, geography, and deep-rooted exchange between Portugal and Britain.

Tasting the Aftermath

The Douro’s vineyards endured the thunder of cannon and the smoke of musketry in 1809, yet the rhythm of the river never stopped. Within months of the fighting, rabelos again ferried casks from the upper valley to the Port lodges of Gaia, and merchants once more shipped fortified wine to Britain—the same ally whose soldiers had crossed the Douro under fire. Today, visitors standing on the quays below Porto’s wine houses can still trace the line of that crossing with a glass in hand, tasting a landscape that has survived empires, revolutions, and war.

Weapon Spotlight: Charleville Musket (Modèle 1777, AN IX)

When Marshal Soult’s veterans of Napoleon’s II Corps marched into northern Portugal in 1809, they carried the Charleville musket—the standard arm of the French infantry and one of the most influential weapons of the Napoleonic era. On the hills and riverbanks of Porto, the same musket that had thundered at Austerlitz and Jena fired again, this time across a landscape better known for wine than war.

The Modèle 1777 Charleville, updated under the AN IX reforms of 1801, was a .69-caliber smoothbore flintlock musket weighing just under 10 pounds, with a 44-inch barrel and an iron ramrod. It fired a lead ball wrapped in paper cartridge powder, ignited by a flint striking steel to shower sparks into a priming pan. Its maximum range was about 200 yards, but in practice, trained soldiers fired volleys at 50 to 100 yards—trading precision for speed and density of fire. The average French infantryman could deliver three rounds per minute, a devastating tempo when massed in column or line.

During the First Battle of Porto (29 March 1809), the Charleville’s disciplined volleys gave Soult’s formations a lethal advantage over the poorly armed Portuguese defenders. While Portuguese militia and civic levies fired a patchwork of older flintlocks and hunting guns, the French line regiments maintained the rhythmic cadence of trained musketry—prime, load, present, fire—that broke resistance at the city’s edge. The musket’s socket bayonet, permanently fixed during combat, turned each infantryman into both marksman and pikeman, ideal for storming the crowded streets and quays where Porto fell.

By the Second Battle of Porto (12 May 1809), however, the musket’s limitations were clear. When British troops under Sir Arthur Wellesley established their foothold at the seminary across the Douro, French musketry from the opposite bank proved largely ineffective—the smoothbore’s short range and inaccuracy across open water left defenders exposed to British counterfire and artillery. The Charleville remained reliable in close combat, but on that day, geography and improvisation outweighed firepower.

Still, the Charleville musket symbolized the industrial might and tactical doctrine of Napoleonic France. Standardized at the royal armory in Charleville-Mézières and copied across Europe and America, it was among the first truly mass-produced firearms. American “Brown Bess” muskets and even early U.S. models, like the Springfield 1795, were patterned directly on its design.

At Porto, the Charleville was both tool and testament—an emblem of the professional soldier who marched from Galicia to the Douro and met defeat not through lack of arms, but through audacity from the other side of the river.

The Charleville would serve until replaced by percussion-cap muskets in the 1830s, its lineage shaping firearms on both sides of the Atlantic. Yet in May 1809, amid the smoke over the river and the cellars of Porto, it represented the apex of an era—where disciplined volleys and cold steel still ruled the field, even as a new age of precision loomed on the horizon.

Design Legacy: The Lineage of the Charleville

The Charleville musket was the culmination of more than a century of French innovation in small arms design. Its origins stretched back to the early 1700s, when France sought to impose order and uniformity on its army’s chaotic mix of weapons. Under Louis XV, the crown established official “pattern muskets,” beginning with the Model 1717, the first standardized firearm ever adopted by a national army. Over the next sixty years, armories at Charleville, Maubeuge, and St. Étienne refined that pattern, creating lighter, more reliable weapons that could be built interchangeably across arsenals.

By the eve of the French Revolution, this effort produced the Modèle 1777, a sleek, well-balanced smoothbore flintlock musket that quickly became the pride of Europe’s most powerful army. Yet revolution brought both opportunity and chaos. When the monarchy fell and the Republic rose, France faced a new problem: how to arm hundreds of thousands of conscripts with limited industrial capacity. The answer came in the “AN IX reforms”—a sweeping reorganization of weapons design and production enacted during Year IX (1800–1801) of the Revolutionary Calendar.

The AN IX (An Neuf) reforms were more than a simple update to the 1777 musket; they reflected the needs of a revolutionary army fighting wars on every front. The reforms simplified the musket’s construction for mass production, standardized the lock mechanism, and replaced delicate brass fittings with more durable iron. The goal was practical: make the weapon faster and cheaper to build, easier to repair in the field, and consistent across France’s decentralized armories. The resulting Modèle 1777 AN IX became the primary firearm of Napoleon’s armies—issued in the hundreds of thousands to line infantry across Europe.

In essence, the AN IX Charleville was a weapon of the Industrial Revolution’s dawn. It embodied precision manufacturing before true mechanization existed, a bridge between handcrafted muskets and the era of assembly-line rifles to come.

Its influence spread far beyond France. The newly formed United States Army modeled its first official musket, the Springfield Model 1795, directly on the Charleville pattern. American arms produced at Springfield Armory and Harpers Ferry adopted its dimensions, lock design, and even its brass hardware. For half a century, nearly every U.S. military musket owed something to French engineering.

Even as technology advanced—first to percussion caps, then to rifled barrels—the Charleville’s proportions and mechanical simplicity remained the blueprint for 19th-century infantry weapons. In a very real sense, the musket carried by Soult’s veterans at Porto was the ancestor of the Springfield rifles carried by American soldiers a generation later.

The AN IX reforms thus mark a pivotal moment in military history: when France transformed a finely crafted weapon into a system of production, arming not just soldiers, but an empire.