Overview: A Crossroads of Culture and Conflict

Northeast Italy has long been a contested frontier where geography, culture, and empire has collided for millennia. The regions of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Veneto, and Trentino-Alto Adige have seen centuries of shifting borders and competing rulers. Early on, the area was home to the Veneti and Celtic tribes before becoming part of the Roman Empire. After Rome’s fall, the region passed through the hands of the Ostrogoths, Lombards, and eventually the Carolingian Empire.

From the Middle Ages and Renaissance and into the 19th and 20th centuries, the patchwork continued. Venice grew into a maritime powerhouse, ruling much of the Adriatic and eastern Veneto. Meanwhile, the Habsburgs extended their reach into Trentino and South Tyrol, territories they would hold until World War I.

During Italy’s 19th-century unification, the region continued to be a political and military battleground. While Veneto joined the Kingdom of Italy in 1866, Trentino-Alto Adige and parts of Friuli remained under Austro-Hungarian rule. That division set the stage for the First World War and the front lines would run straight through the vineyards and valleys of region.

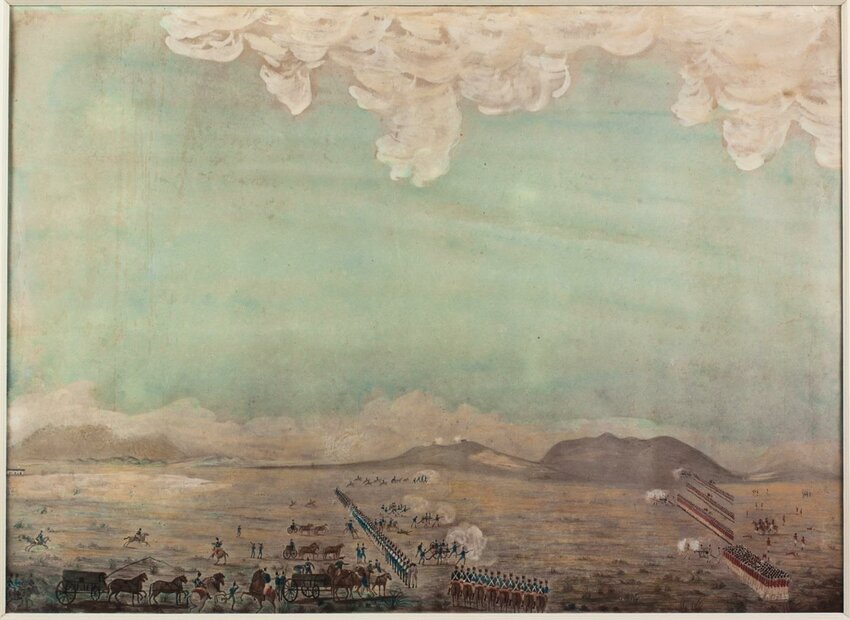

The Battle of Caporetto: The Front Collapses

From 1915 to 1917, the Italian and Austro-Hungarian armies fought brutal battles over mountainous terrain along the Isonzo River and into the Alps. Italy launched eleven significant offensives into modern day Slovenia, but the front barely moved. Then, in October 1917, everything changed.

The Central Powers (Austro-Hungarian forces reinforced by experienced German troops) launched a surprise attack near the town of Caporetto (modern-day Kobarid, Slovenia). Based on their previous eleven assaults, Italian commanders considered the terrain in the area too rugged for a large-scale assault. That miscalculation proved costly as the Italian army now faced battle-hardened German units rather the same Austro-Hungarian forces they had matched over the past two plus years.

At 2:00 a.m. on October 24, the Germans opened with a gas bombardment. Chlorine and phosgene shells blanketed Italian lines. As the gas lifted, German stormtroopers, small, elite infantry units trained in rapid movement and infiltration, began their advance. They moved quickly through foggy mountain passes, bypassed strongpoints, and quickly cut Italian communications.

What followed was not the slow trench warfare Italy had known. It was fast, mobile, and precise. Using flamethrowers, portable machine guns (see Section 3 about the Madsen light machine gun), and surprise, German and Austro-Hungarian troops climbed mountain trails, seized key terrain, and created panic behind enemy lines.

Italian forces, many made up of undertrained conscripts and exhausted veterans, crumbled. Command collapsed. Units retreated chaotically or surrendered en masse. In just 48 hours, the enemy advanced nearly 20 miles—an astonishing pace for the time. By early November, the Italians had abandoned the Isonzo front and retreated all the way to the Piave River, not far from Venice.

Erwin Rommel at Caporetto: The Württemberg Mountain Battalion

When most people hear the name Erwin Rommel, they think of German tanks sweeping across the North Africa in World War II. But twenty plus years earlier in the cold Julian Alps, Rommel led a small force of mountain troops during the Battle of Caporetto.

Rommel was a 25-year-old Oberleutnant (First Lieutenant) in the Württembergisches Gebirgsbataillon, an elite German mountain infantry unit specially trained for high-altitude warfare. This battalion was attached to the German 14th Army, part of the joint German–Austro-Hungarian force deployed to break the stalemate on the Italian Front.

Rommel’s orders were to push through the rugged mountain terrain, flank the Italian defenses, and seize key strategic positions. He greatly exceeded those expectations.

Rommel and his men crossed into Italy through the Krn Mountains (the Italians referred to it as the Monte Nero region), part of the Julian Alps near the Isonzo River. He maneuvered through steep ravines and over high-altitude ridges, often at night, and often without established paths. His route took him Mount Matajur, a strategic peak that guarded the approaches to the Friuli plain. It is one of the areas that the Italian Army believed that no sizable force could pass through it. With fewer than 200 men, Rommel scaled the mountain under heavy fire, advanced through enemy trenches, and forced multiple Italian units to surrender. He captured five Italian positions in 52 hours, with minimal rest and few losses. The fall of Matajur opened the door to the Tagliamento River, deep inside Italian territory, and helped collapse the entire Italian Second Army front.

In his postwar memoir Infanterie greift an (Infantry Attacks), Rommel wrote that his unit’s total casualties were minimal yet he reported that he captured over 9,000 Italian prisoners including 150 officers and 81 artillery pieces. For his actions, Rommel received the Pour le Mérite, Germany’s highest military honor.

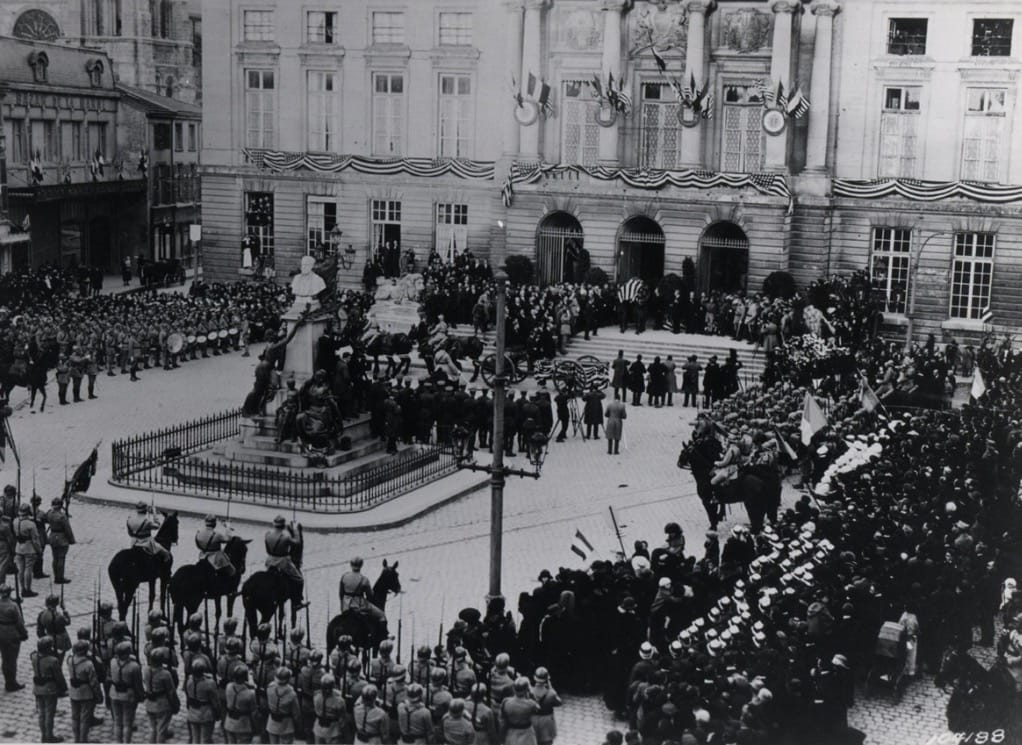

In total, over 40,000 Italians were killed or wounded, 280,000 taken prisoner, and hundreds of thousands deserted. It was a disaster that shook Italy to its core. The Allies rushed in British and French reinforcements to prevent a complete collapse. General Cadorna was replaced by General Armando Diaz, who worked to rebuild morale and modernize Italy’s defensive strategy. Eventually, the line held at the Piave River. One year later, Italy delivered a decisive counterblow at Vittorio Veneto.

The Vineyards of the Front: Wine Regions in the War Zone

Italian Denominazione di Origine—“designation of origin.”

Italy recognizes its wine-producing regions through a strict classification system rooted in both geography and tradition, balancing centuries of local viticulture with modern regulatory oversight. This system is overseen by the Italian Ministry of Agriculture and primarily operates through a tiered designation structure that ensures wines are tied to their place of origin and adhere to quality standards.

At the foundation of this recognition is the concept of Denominazione di Origine—“designation of origin.” The most prestigious classifications are DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita) and DOC (Denominazione di Origine Controllata). DOCG represents the highest level, requiring rigorous testing, strict production rules, and guaranteed quality. Wines labeled DOC follow similarly strict rules but with slightly less oversight. Both classifications define geographical boundaries, permitted grape varieties, yield limits, aging requirements, and winemaking techniques.

Below these, there is the IGT (Indicazione Geografica Tipica) designation, introduced in 1992 to allow more flexibility. IGT wines still reflect a specific region but permit more experimentation with grape varieties and methods—often used by innovative producers crafting high-quality wines outside traditional norms, like the famed Super Tuscans.

Each recognized region—whether broad areas like Tuscany or specific zones like Barolo—is mapped and legally defined, with producers needing to follow the codified rules to use the regional name on the label. Italy has over 330 DOC and DOCG zones and more than 100 IGTs, each representing a unique combination of soil, climate, and culture. Together, these designations uphold Italy’s deep connection between land and wine, preserving local identity while promoting excellence.

1. Veneto: Home of Prosecco and Amarone

Terrain and Soil:

Veneto is a diverse wine region in northeastern Italy stretching from the Dolomites in the north to the Adriatic Sea in the south. Key subregions include Valpolicella, Soave, and the Prosecco Hills around Conegliano and Valdobbiadene. The terrain includes alpine foothills, rolling hills, and broad river plains. Soils vary widely from volcanic in Soave, limestone and moraine near Lake Garda, and alluvial and gravelly along the Piave River, where Italian forces halted the Austro-German advance after Caporetto. The climate ranges from cool alpine to humid continental and Mediterranean, offering ideal conditions for both sparkling and still wines.

Grapes Grown:

- Whites: Glera (for Prosecco), Garganega (Soave), Pinot Grigio

- Reds: Corvina, Rondinella, Molinara (used in Amarone and Valpolicella)

Wines Produced:

- Prosecco DOC/DOCG: Crisp sparkling white, often from Conegliano-Valdobbiadene

- Amarone della Valpolicella: Powerful, dry red made from semi-dried grapes

- Soave DOC: Fresh, mineral-rich white from volcanic soils

- Valpolicella & Ripasso: From light and fruity to deep and robust

Historical Roots:

Viticulture here dates back to the Veneti and Romans. Winemaking expanded under Venetian rule, becoming a trade commodity across Europe.

2. Trentino-Alto Adige

Terrain and Soil:

Trentino-Alto Adige is a mountainous region in northern Italy, bordered by Austria and Switzerland. Vineyards rise along steep Alpine slopes, from valley floors around 650 feet above sea level to elevations above 3,300 feet. The terrain is shaped by glacial activity and tectonic uplift, with soils composed of dolomitic limestone, granite, and moraine deposits. These varied, mineral-rich soils, combined with a cool Alpine climate and dramatic diurnal temperature shifts, produce incredible wines.

Grapes Grown:

- Trentino

- Whites: Nosiola

- Reds: Teroldego, Marzemino

- Alto Adige (Südtirol):

- Whites: Gewürztraminer, Pinot Bianco

- Reds: Lagrein, Schiava, Pinot Nero

Wines Produced:

- Trento DOC: Traditional-method sparkling wine

- Lagrein & Schiava: Indigenous reds from Alto Adige

- Elegant whites: Clean, varietal wines influenced by cooler climates

Historical Roots:

Winegrowing dates to Celtic and Roman times, and the Austro-Hungarian legacy still influences winemaking today in grape choice.

3. Friuli-Venezia Giulia

Terrain and Soil:

Friuli-Venezia Giulia lies in Italy’s northeast corner, bordered by Austria, Slovenia, and the Adriatic Sea. The region spans from Alpine foothills in the north to low-lying coastal plains in the south. Key subregions like Collio and Colli Orientali feature flysch soils comprised of marl and sandstone, which retain water and minerals making it ideal for white wine grapes. The Grave area is known for its gravelly alluvial plains. A blend of Alpine coolness and maritime influence helps preserve acidity and aromatic complexity, making Friuli one of Italy’s leading regions for age-worthy, structured white wines.

Grapes Grown:

- Whites: Friulano, Ribolla Gialla, Malvasia Istriana, Sauvignon Blanc

- Reds: Refosco dal Peduncolo Rosso, Schioppettino, Pignolo

Wines Produced:

- Collio DOC & Friuli Colli Orientali: Complex whites, including skin-contact “orange” styles

- Grave del Friuli DOC: Known for international varieties, especially Pinot Grigio

- Picolit: Sweet wine with deep local heritage

Historical Roots:

While winemaking dates to Roman times, Friuli led the modern Italian white wine revolution in the 1970s, emphasizing stainless steel, clean flavors, and varietal expression.

Slovenian Regions

Primorska (The Littoral Region)

There are three main wine regions in Slovenia. In the northeast, Podravska borders Croatia and Hungary. It is best known for sparkling wines and dessert wines. Posavska is in the southeast and borders Croatia. Primorska borders Italy’s Friuli-Venezia Giulia and shares similar geography, soil, and grape varieties. Primorska is divided into four sub-regions:

1. Goriška Brda

Terrain and Soil:

Goriška Brda is a hilly region nestled between the Julian Alps and the Adriatic Sea, sharing a border with Italy’s Collio region. The terrain is composed of gentle slopes with flysch soil, a layered mix of marl and sandstone, which retains water and minerals. The climate is a blend of Alpine and Mediterranean influences, providing warm days and cool nights that help preserve acidity in grapes.

This region is sometimes referred to as Slovenia’s Tuscany and many of the vineyards here are terraced due to erosion.

Grapes Grown:

- Whites: Rebula (Ribolla Gialla), Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Pinot Gris

- Reds: Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir

Wines Produced:

Goriška Brda is well known for white wines, especially Rebula, which can be made in a variety of styles to included aged or orange wines with extended skin-contact. Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay tend to be crisp and mineral-driven. The region also produces exceptional red wines, particularly Merlot and Bordeaux-style blends.

Historical Roots:

Viticulture in Goriška Brda dates back to Roman times, with local continuity through the medieval period under Venetian and later Habsburg control. After WWII, the region was divided between Italy and Yugoslavia, but winemaking persisted. Since Slovenia’s independence in 1991, Goriška Brda has emerged as a world-class wine region, hence the comparison to Tuscany.

2. Vipava Valley (or Vipavska Dolina)

Terrain and Soil

The Vipava Valley lies between the Trnovo Plateau and Nanos Mountains, forming a funnel for both Mediterranean warmth and the strong Bora winds from the northeast. The Bora winds are known to gust at wind speeds as high as 100mph or more. Soils are a mix of marl, clay, and limestone, with well-drained slopes and river plains that vary in elevation and exposure, making it a region with significant diversity in its microclimates.

Grapes Grown

- Whites: Zelen, Pinela, Klarnica, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc

- Reds: Barbera, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Malvasia

Wines Produced

Vipava Valley is especially known for its unique native white varieties, such as Zelen and Pinela, which produce floral and aromatic wines. In addition, orange wines are increasing produced. The valley also produces complex reds from Merlot and Barbera.

Historical Roots

Winegrowing has existed in the Vipava Valley since Roman antiquity. The valley was historically a trade route between Central Europe and the Adriatic.

3. Kras (Karst)

Terrain and Soil:

The Kras (Karst) Plateau is a rugged limestone region sitting just above the Gulf of Trieste, stretching along the Italian border. The landscape is rocky, dry, and windswept, with thin topsoil composed of terra rossa, a red, iron-rich clay over hard limestone. This harsh environment yields low yields but high-quality, deeply mineral wines.

Grapes Grown:

- Whites: Malvasia Istriana

- Reds: Terrano (Refosco varietal), Vitovska, Cabernet Franc

Wines Produced

Many consider Terrano, a deep red wine with high acidity, dark fruit, and an earthy, iron-rich character as the standout from Kras. In addition, Malvasia Istriana produces aromatic white wines with good minerality.

Historical Roots

Winemaking in the Karst dates back to pre-Roman times, with the region playing a vital role in ancient viticulture. It was later influenced by Roman, Venetian, and Habsburg rule. The name “Karst” gave rise to the term for limestone landscapes worldwide.

4. Slovenska Istra (Slovenian Istria)

Terrain and Soil:

Slovenska Istra is located in southwestern Slovenia along the Adriatic coast, bordering Italy and Croatia. The terrain is made up of rolling coastal hills and valleys with a Mediterranean climate, hot, dry summers and mild winters. Soils are primarily flysch, a mix of marl and sandstone, with some areas of clay and limestone. The proximity to the sea provides beneficial humidity and maritime breezes, which provides ideal condition to ripen grapes.

Grapes Grown:

- Whites: Malvazija (Malvasia Istriana), Rumeni Muškat (Yellow Muscat), Chardonnay

- Reds: Refošk (Refosco), Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah

Wines Produced

The region produces big red wines from Refošk, which provides deep color, high acidity, and bright red fruit. Malvazija is considered the flagship white—aromatic, crisp, and mineral-rich. Rumeni Muškat is used for semi-sweet and dessert wines.

Historical Roots

Wine production in Istria began over 2,000 years ago with Illyrian and Roman cultivation, and continued under Byzantine, Venetian, and Austro-Hungarian rule. Slovenska Istra has a significant wine culture and since Slovenia independence, the region has seen a revival of native grapes and traditional techniques.

Weapon Spotlight: The Madsen Light Machine Gun

The Central Powers’ breakthrough at Caporetto wasn’t just a tactical surprise—it was powered by a new kind of weapon, the Madsen light machine gun. The Madsen was the world’s first mass-produced, shoulder-fired automatic weapon.

Developed in Denmark in the 1890s, the Madsen was the brainchild of Captain Vilhelm Madsen and engineer Julius Rasmussen. It was later refined by Theodor Schouboe and by 1902, it was in mass production—and adopted by armies worldwide. What set this weapon apart was its mobility. Weighing around 20 pounds and fed by a curved magazine on top (which could hold between 25–40 rounds), it could be fired from the shoulder, a bipod, or a simple mount. It was a rare blend of firepower and portability.

(I highly recommend watching this YouTube video by user “vbbsmyt” who creates incredibly detailed animations of the workings of many weapons. His video on the Madsen is simply amazing! Link here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LH5tgFEfzaU.)1

Why It Mattered at Caporetto

German stormtroopers needed weapons they could carry through mountain passes and fire on the move. The Madsen delivered. Unlike the bulky, belt-fed guns commonly used in WWI trenches, it allowed small units to lay down suppressing fire and keep advancing, perfect for the steep valleys and forests of the Julian Alps.

Its recoil-based firing system, while mechanically complex, worked reliably in harsh field conditions. It allowed for quick follow-up shots and fast magazine changes—critical for fast-moving infiltration tactics.

Pros and Cons

Strengths:

- Light enough for mobile infantry

- Faster reloads than belt-fed guns

- Performed well in mountain warfare

Limitations:

- Smaller magazines meant more frequent reloads

- Modest rate of fire by later standards (~450 rounds/min)

- Mechanically complex, requiring good maintenance

Still, at Caporetto, the Madsen gave German and Austro-Hungarian troops a vital edge—especially in terrain that punished slower, heavier weapons.

Lasting Legacy

The Madsen’s influence extended well beyond WWI. Its top-mounted magazine design inspired later weapons like the British Bren gun, and its durability made it a favorite across the globe. Incredibly, some military and police forces kept using it into the late 20th century.

Its original design was protected by patents, including a 1901 model highlighting its unique firing system—a testament to how far ahead of its time the Madsen truly was.

In Conclusion

From Vineyards to Trenches and Back Again

The story of Caporetto is more than just military history. It’s also a story of terrain, adaptation, and innovation—where ancient wine regions became battlegrounds, and new technologies like the Madsen light machine gun reshaped how wars were fought in the modern age.

Watch for upcoming blogs that will explore specific sites to trace the battle of Caporetto as well as specific winery visits!

Sources

Books2

D’Agata, Ian. Native Wine Grapes of Italy. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014.

Websites

“Battle of Caporetto 1917, Italian Front, First World War.” Imperial War Museums Collections, accessed July 1, 2025. https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/search?filters%5BeventString%5D%5BBattle%20of%20Caporetto%201917%2C%20Italian%20Front%2C%20First%20World%20War%5D=on.

“The Battle of Caporetto: Strategy | Consequences | Historical.” educba.com. Accessed July 1, 2025. https://www.educba.com/the-battle-of-caporetto/.

“Digital History Center – Atlases.” United States Military Academy at West Point. Accessed July 1, 2025. https://www.westpoint.edu/research/west-point-werx/digital-history-center/digital-history-center-atlases.

Grillini, Anna. “Caporetto, Battle of.” 1914–1918 Online: International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Last updated April 28, 2015. Accessed July 1, 2025. https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/caporetto-battle-of/.

“Madsen Light Machine Gun: A True Centennial Weapon.” The Armory Life, January 30, 2024. Accessed July 1, 2025. https://www.thearmorylife.com/madsen-light-machine-gun/.

Robinson, Andrea. “The Wines of Northeast Italy.” Andrea Wine. Accessed July 1, 2025. https://andreawine.com/wines-northeast-italy/.

“Slovenian Wine.” Think Slovenia. Accessed July 1, 2025. https://www.thinkslovenia.com/info-activities/slovenian-wine#goriska-brda-primorska-wine-region.

“Wines of Slovenia.” I Feel Slovenia (Slovenian Tourist Board), accessed July 1, 2025. https://www.slovenia.info/en/things-to-do/food-and-wine/wines-of-slovenia.

“Wine Map of Italy.” Vineyards. Accessed July 1, 2025. https://vineyards.com/wine-map/italy.

- I cannot embed this video in my post as the video creator does not allow that option. I recommend following the link to YouTube as it provides an amazing look at the inner workings of this incredible light machine gun. Link again for convenience: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LH5tgFEfzaU ↩︎

- Note, the Amazon links to the published sources utilize my associates link. ↩︎

Share this post: