A Gateway to Sicily

Sicily has always been more than just the Mediterranean’s largest island—it has been the crossroads of civilizations. Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Normans, and Spanish all left their mark on its shores. For the ancient world, Sicily was a jewel: fertile farmland, abundant trade routes, and a stepping stone between Africa and Europe.

By the 5th century BCE, the island was divided between Greek colonies in the east and south and Carthaginian settlements in the west. Himera, a Greek colony founded in 648 BCE by settlers from Zancle (Messina) and Syracuse, stood on the island’s north coast near modern Termini Imerese. Its location made it a frontier town, perched on the boundary where Greek and Carthaginian ambitions collided. Twice in history, Himera became the site of decisive clashes—the Battles of Himera (480 BCE and 409 BCE).

The First Battle of Himera (480 BCE)

To understand the battle, one must first understand Carthage. Founded centuries earlier by Phoenician traders from Tyre, Carthage had grown into a naval and trading empire based in modern-day Tunisia. By the 5th century BCE, it commanded colonies across North Africa, Sardinia, western Sicily, and beyond. Carthage’s wealth came from commerce, and its armies were built not from citizen levies but from mercenaries — Iberian swordsmen, Balearic slingers, Numidian cavalry — all led by Carthaginian generals.

The invasion of 480 BCE was led by Hamilcar, one of Carthage’s most prominent generals. He came to Sicily not only to expand Carthaginian power but also to restore Terillus, the ousted ruler of Himera. Terillus was a tyrant, a term in the Greek world that did not mean cruel despot as it does today, but rather a sole ruler who gained power outside the traditional aristocratic or democratic systems. Tyrants could be enlightened reformers or ruthless autocrats; what mattered was that they ruled alone, often supported by mercenary forces. Terillus had been expelled by Theron of Acragas (modern Agrigento), and Carthage saw an opportunity to intervene.

Against this force stood the Greeks under Gelon, tyrant of Syracuse. Gelon, like Terillus, bore the title of tyrant. Unlike Terillus, Gelon was both a shrewd strategist and a popular leader. Under his rule, Syracuse had grown into the most powerful Greek city on Sicily. Gelon brought with him not only soldiers but also a disciplined military system centered on the phalanx.

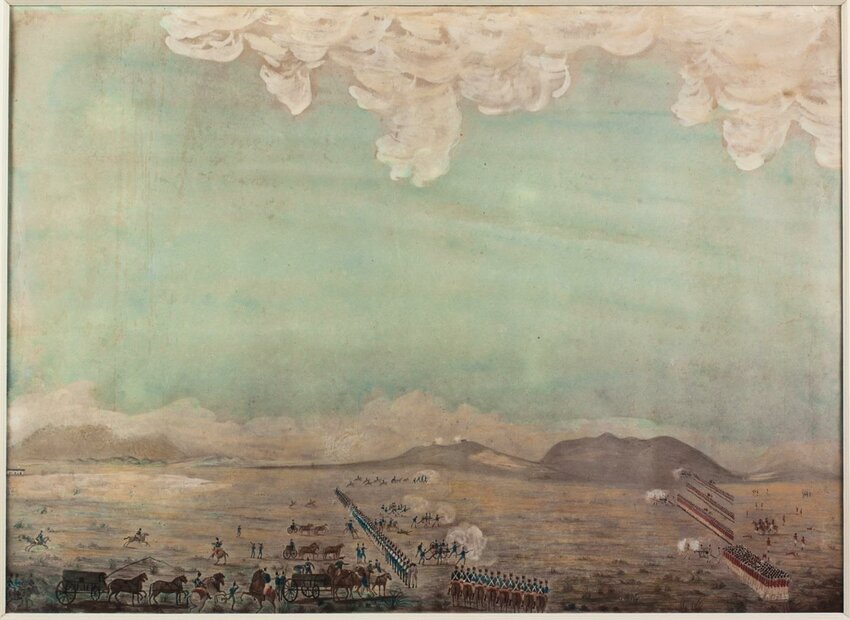

The phalanx was the backbone of Greek warfare: a tight formation of hoplite infantry, each man bearing a large round shield (aspis) and a long spear (dory). Packed shoulder to shoulder, the phalanx created a wall of bronze and wood, advancing as a single unit. Its strength lay in discipline and unity: a lone hoplite was vulnerable, but a phalanx could punch through even larger, less organized forces.

The battle itself was a mixture of stratagem and brute force. Gelon executed a bold ruse: some of his cavalry disguised themselves as allies of Carthage, infiltrated Hamilcar’s camp, and set it ablaze. Ancient sources say Hamilcar perished in the flames — some accounts even describe him dying while performing a sacrificial ritual. As the Carthaginian camp burned, Gelon’s hoplites advanced in their phalanx, spears bristling. The mercenary army, caught off guard and suddenly leaderless, broke and fled.

The victory was decisive. Greek writers later hailed it as the “Salamis of the West”, noting that it occurred in the same year (480 BCE) as the Greek naval victory over Persia at Salamis. Both, they claimed, were struggles of free Greek states resisting foreign domination. For nearly seventy years after Himera, Carthage refrained from sending another major expedition to Sicily.

The Second Battle of Himera (409 BCE)

But memory runs long in the Mediterranean. In 409 BCE, Hannibal Mago, grandson of Hamilcar, led a Carthaginian army back to Himera. Hannibal Mago should not be confused with the far more famous Hannibal Barca, who fought Rome centuries later at Cannae; but he belonged to the same aristocratic family that produced many of Carthage’s leading generals. His campaign was driven by revenge — both personal and political.

This time, Carthage brought not only numbers but also siege technology. Hannibal’s army included battering rams, siege towers, and stone-throwing catapults, devices rarely seen in Greek Sicily. His forces were, as always, multinational: Iberian heavy infantry, Balearic slingers with deadly range, and swift Numidian cavalry.

The defenders of Himera, reinforced by contingents from Syracuse and Agrigento, fought bravely. But the city could not withstand the Carthaginian machines. Hannibal’s troops methodically battered the walls and stormed the breaches. When the city fell, Hannibal exacted a brutal vengeance. Ancient sources tell of thousands of inhabitants executed or enslaved, and in a grim act of symbolism, he sacrificed three thousand Greek prisoners at the spot where his grandfather had died. Himera itself was razed to the ground. Survivors were resettled nearby at Thermae Himerenses (modern Termini Imerese).

Archaeology Confirms the Battles

For centuries, the battles of Himera lived in the pages of Greek historians. But in the early 2000s, archaeologists uncovered mass graves near Himera’s ruins that provided tangible proof of the scale of fighting. Hundreds of skeletons were found, many bearing signs of violent death — cuts, blunt trauma, and embedded arrowheads. The graves matched the dates of 480 and 409 BCE, giving powerful confirmation that Himera had indeed seen two catastrophic clashes. The discovery transformed Himera from legend into lived history, with human remains testifying to the bloodshed described in ancient texts.

Himera in the Shadow of the Punic Wars

The two Battles of Himera were not isolated events. They were part of the long Greco-Carthaginian struggle for Sicily, a contest of cultures, economies, and armies. That struggle would eventually draw in a third superpower: Rome. By the 3rd century BCE, disputes over Sicily ignited the First Punic War (264–241 BCE), the opening chapter of Rome’s century-long rivalry with Carthage.

In hindsight, the story of Himera foreshadowed that greater conflict. The city’s fate reflected Sicily’s destiny: a land too strategic to remain independent, destined instead to be the battlefield where empires met. First Greeks and Carthaginians, then Romans and Carthaginians.

Northern Sicily: Vineyards of Himera

Terrain and Soil:

The site of ancient Himera lies along Sicily’s north-central coast near modern Termini Imerese, where coastal plains meet the rugged Madonie mountains. This terrain once made Himera a strategic frontier between Greek colonies in the east and Carthaginian holdings in the west. Today, vineyards stretch across rolling hills of limestone, clay-limestone, and marl, nourished by maritime breezes from the Tyrrhenian Sea. The inland slopes benefit from higher elevations and cooler nighttime temperatures, which preserve acidity and aromatic freshness in the grapes. Just as the landscape once balanced power between empires, it now balances warmth and freshness in viticulture.

Grapes Grown:

- Whites: Catarratto, Inzolia, Grillo, Chardonnay

- Reds: Nero d’Avola, Perricone, Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon

Wines Produced:

Contea di Sclafani DOC: This inland appellation, encompassing the hills around Termini Imerese, produces structured reds from Nero d’Avola and earthy, spicy wines from Perricone, once a nearly forgotten local grape. Whites made from Catarratto and Inzolia are crisp and mineral-driven, echoing the limestone soils of the Madonie foothills.

Sicilia DOC: The broad island-wide appellation also covers the Himera region, offering an array of styles. Bold Nero d’Avola blends, elegant single-varietal Grillo whites, and international styles like Syrah and Chardonnay highlight both the adaptability and the depth of Sicily’s modern wine identity.

Historical Roots:

Viticulture in Sicily predates the Greek foundation of Himera (648 BCE). The Phoenicians, and later the Greeks, established vineyards along trade routes, recognizing the island’s unique terroir. After the city’s destruction by Carthage in 409 BCE, the surrounding land remained contested for centuries, later falling into Roman hands during the Punic Wars. Roman colonists formalized viticulture, integrating Sicilian wines into Mediterranean trade networks. Over time, what was once a frontline battlefield evolved into a landscape of agricultural continuity—where vines replaced fortifications, and terroir preserved a legacy older than empire.

Weapon Spotlight: Greek dory spear

When the armies clashed at the First Battle of Himera in 480 BCE, the fate of Sicily turned on a weapon as simple as it was formidable: the Greek dory spear. To the men of Syracuse and Acragas who formed the hoplite ranks, the dory was not merely a tool of war but the very symbol of their role as citizen-soldiers. Owning such a spear — with its ash-wood shaft, iron tip, and heavy bronze butt-spike known as the sauroter or “lizard-killer” — meant you stood ready to defend your polis.

In battle, the dory transformed individuals into a single, unified machine. Arrayed in the tight formation of the phalanx, each man’s spear projected beyond the shield of his comrade, creating a forest of points bristling toward the enemy. Victory did not come from lone feats of swordplay but from the relentless pressure of shield against shield, spearpoint against flesh. At Himera, Gelon’s hoplites advanced in just such a wall of bronze and wood, thrusting their dories forward in unison. The Carthaginian army was larger, but it lacked the cohesion of the phalanx. When Gelon’s men burst into their camp, their discipline and their spears carried the day.

The strengths of the dory were clear: it was long enough to strike over or around an enemy’s shield, sturdy enough to withstand the crash of formations, and versatile thanks to the sauroter, which doubled as a secondary point if the spearhead broke. Yet it had weaknesses too. In tight ranks it was devastating, but outside the phalanx the dory was awkward. A lone soldier with a heavy shield and spear was slow compared to light infantry, and once combat closed to sword-range, the weapon lost much of its advantage.

Even so, the legacy of the dory was profound. It set the standard for the spear as the primary infantry weapon in the Mediterranean for centuries. Macedon’s Philip II and Alexander the Great lengthened it into the sarissa, a pike that made the Macedonian phalanx nearly unstoppable. Roman legions, though they relied on the short stabbing sword, still recognized the value of the spear, adopting the pilum as their opening missile. The principle that victory lay in disciplined ranks of spearmen would echo from the battlefields of Sicily to those of medieval Europe, shaping everything from Swiss pikemen to Renaissance mercenary companies.

Centuries later, Greek pottery still depicted hoplites marching with their dories raised upright — a quiet reminder of civic duty and shared defense. The weapon endured in memory long after Himera itself was destroyed.

Sources:

Ancient Sources

- Diodorus Siculus. Library of History. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. 12 vols. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1933–1967.

- Herodotus. The Histories. Translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt, revised by John Marincola. London: Penguin Classics, 2003.

Modern Scholarship

- Hoyos, Dexter. The Carthaginians. New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Lazenby, J. F. The First Punic War: A Military History. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996.

- Serrati, John. “Warfare and the State: The Classical World.” In The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare, edited by Philip Sabin, Hans van Wees, and Michael Whitby, 2 vols., 1: 387–427. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Strauss, Barry S. The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter that Saved Greece—and Western Civilization. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004. (for comparative context with Salamis, often linked with Himera).

Archaeological Reports

- De Angelis, Franco. “Going against the Grain in Sicilian Greek Economics.” Phoenix 51, no. 3/4 (1997): 223–237.

- Sagnotti, Leonardo, et al. “Archaeomagnetic Dating of Two Ancient Battlefields at Himera (Sicily, Italy).” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113, no. 47 (2016): 13462–13467.

- Vassallo, Stefano. “The Necropolises of Himera.” In Sicily: Art and Invention between Greece and Rome, edited by Claire L. Lyons, Michael Bennett, and Clemente Marconi, 54–63. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013.