In January 1806, British and Batavian troops faced each other on the low coastal plain north of Cape Town. The fight at Blaauwberg was brief, but its outcome determined who would control one of the most strategic points on the globe and, indirectly, the vineyards that had taken root on its granite slopes.

The Age of Revolution and the Struggle for Global Trade

From the 1770s to the early 1800s, Europe was convulsed by revolution and war. The American colonies had broken from Britain, and France’s own revolution in 1789 overturned monarchies and spread conflict across the continent. These upheavals extended far beyond Europe. Wherever empires traded or refueled, their rivalries followed.

For Britain, power depended on its navy and on the long sea route to India and the East Indies, the source of much of its wealth. Steamships and the Suez Canal lay more than half a century in the future; every ship sailing from Portsmouth or London to Calcutta had to follow the winds around the Cape of Good Hope. The voyage was measured in months and could not be made without reliable places to take on food, water, and wine!The victory at Blaauwberg permanently altered the balance of power at the southern tip of Africa. With the Batavian troops defeated and Cape Town surrendered, Britain now controlled the only reliable port between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. From that moment onward, the Cape of Good Hope became an essential link in Britain’s global network of empire—a maritime crossroads that guaranteed safe passage to India, Ceylon, and the rich markets of the East.

The transition from Dutch to British rule brought far-reaching political and cultural changes. The Dutch-speaking burghers, who had lived under VOC governance for more than a century, now found themselves subjects of a new imperial authority. English law replaced Dutch ordinances; trade and shipping realigned toward London rather than Amsterdam. Over time, tensions grew between the Anglicized administration in Cape Town and the Dutch-descended settlers of the interior. Many of those settlers—soon known as Boers or “farmers”—would eventually migrate north and east in search of autonomy, setting in motion the long frontier conflicts that defined the next century of South African history.

Economically, the British occupation opened new markets and transformed the Cape’s modest refreshment station into a commercial port of empire. The region’s wine industry, rooted in Constantia’s 17th-century vineyards, flourished under this new patronage. Exports expanded, and the colony’s most famous product—Vin de Constance, a golden Muscat sweet wine once prized by European nobility—became a favored luxury in Britain’s drawing rooms. The irony was not lost on contemporaries: Napoleon himself, the man whose wars had precipitated the invasion, requested bottles of Constantia during his final exile on St. Helena.

Strategically and symbolically, Blaauwberg marked the end of Dutch influence at the Cape and the beginning of more than a century of British dominance. What had begun as a naval precaution in the Age of Revolution evolved into a permanent colonial presence. From the granite slopes of Constantia to the windswept plains of Blaauwberg, the echoes of that brief January battle carried far beyond the sound of gunfire—into the shaping of a nation, and the long intertwining of empire and wine on Africa’s southern shore.

Since 1652 the Dutch East India Company (VOC) had maintained just such a station at Table Bay, growing produce and planting vines at Constantia and Stellenbosch to keep passing crews healthy. When Revolutionary France conquered the Netherlands in 1795 and created the Batavian Republic, London feared that the Cape would become a French naval base able to threaten Britain’s eastern lifeline. Protecting that route became a matter not of commerce alone but of survival.

Muizenberg 1795: The First British Occupation

Britain struck first. In August 1795, Commodore Sir George Elphinstone and General James Craig anchored off False Bay and defeated the Dutch at the Battle of Muizenberg. The colony was occupied, giving Britain a secure port halfway to India. For ten years British officers garrisoned Cape Town and drank the local Vin de Constance, a Muscat-based sweet wine already famous in Europe.

Peace between Britain and France in 1802 briefly reversed the situation. Under the Treaty of Amiens, the Cape returned to Batavian hands, though the Dutch remained under French influence. When war resumed a year later and Napoleon crowned himself emperor, London again saw the Cape as a weak link in a chain it could not afford to lose.

The 1806 Campaign

In the autumn of 1805, as the War of the Third Coalition pitted Britain and its allies against Napoleonic France, the Admiralty dispatched an expedition to retake the Cape before France could move. The force, about 5,000 men under Lt. Gen. Sir David Baird and Rear Admiral Sir Home Riggs Popham, sailed from Madeira, rounded the Atlantic, and reached the coast in early January 1806.

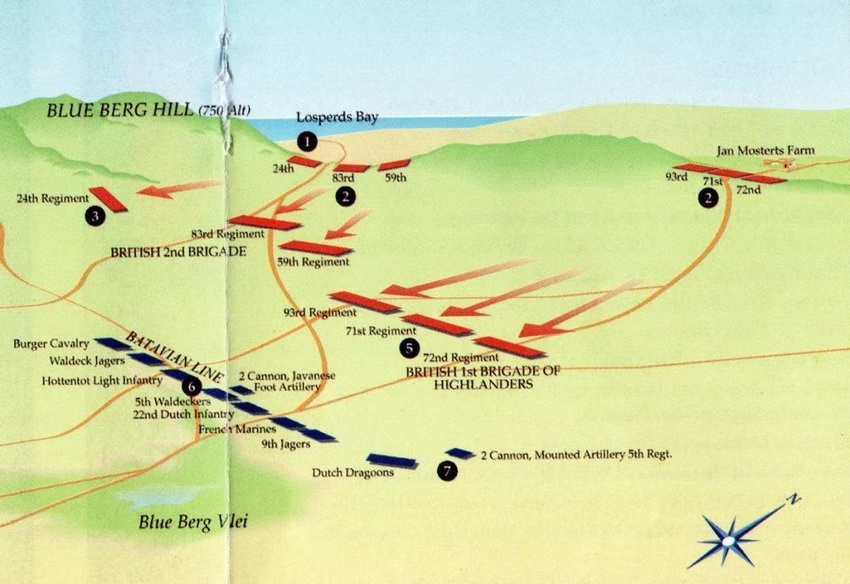

The Batavian governor, Gen. Jan Willem Janssens, mustered roughly 2,000 troops: regulars, local burgher militia, and Cape-born auxiliaries. He established a defensive line across the plain near Blaauwberg, the “Blue Mountain” ridge north of Cape Town, hoping to delay the invaders until reinforcements (or diplomacy) could intervene.

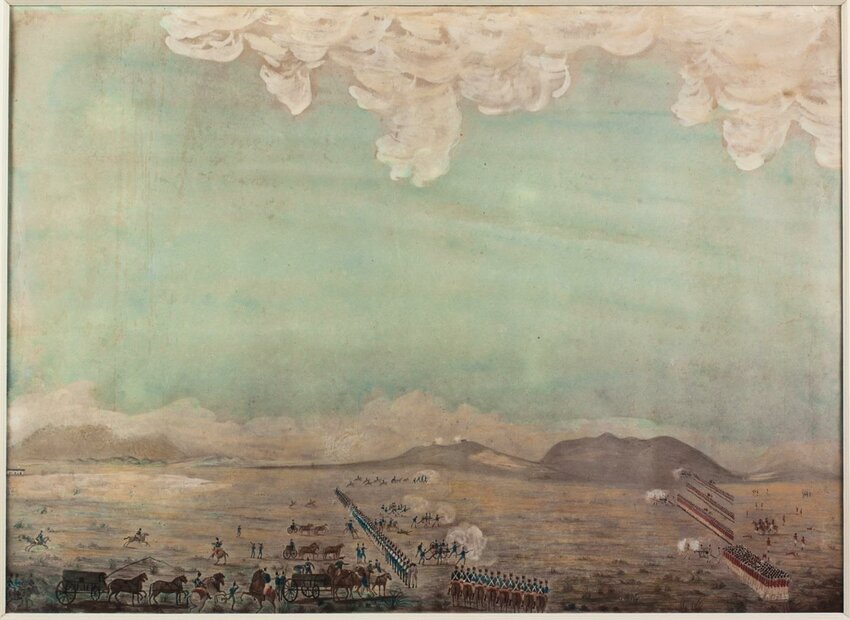

The Battle

At dawn on 8 January 1806, Baird’s troops advanced southward from Melkbosstrand. Two Highland regiments led the assault while Royal Navy guns supported from offshore. The British line maintained its cohesion under sporadic fire until it closed with Janssens’s force. Within hours, the Batavian formation buckled under superior numbers and discipline. Janssens withdrew toward Stellenbosch, leaving the approaches to Cape Town undefended.

On 10 January, Cape Town capitulated. The British had lost fewer than 200 men; the Batavian defenders, roughly 700. The outcome was decisive.

Consequences and Legacy

The victory at Blaauwberg permanently altered the balance of power at the southern tip of Africa. With the Batavian troops defeated and Cape Town surrendered, Britain now controlled the only reliable port between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. From that moment onward, the Cape of Good Hope became an essential link in Britain’s global network of empire, a maritime crossroads that guaranteed safe passage to India, Ceylon, and the rich markets of the East.

The transition from Dutch to British rule brought far-reaching political and cultural changes. The Dutch-speaking burghers, who had lived under VOC governance for more than a century, now found themselves subjects of a new imperial authority. English law replaced Dutch ordinances; trade and shipping realigned toward London rather than Amsterdam. Over time, tensions grew between the Anglicized administration in Cape Town and the Dutch-descended settlers of the interior. Many of those settlers—soon known as Boers or “farmers”—would eventually migrate north and east in search of autonomy, setting in motion the long frontier conflicts that defined the next century of South African history.

Economically, the British occupation opened new markets and transformed the Cape’s modest refreshment station into a commercial port of empire. The region’s wine industry, rooted in Constantia’s 17th-century vineyards, flourished under this new patronage. Exports expanded, and the colony’s most famous product, Vin de Constance, a golden Muscat sweet wine once prized by European nobility, became a favored luxury in Britain’s drawing rooms. The irony was not lost on contemporaries: Napoleon himself, the man whose wars had precipitated the invasion, requested bottles of Constantia during his final exile on St. Helena.

Strategically and symbolically, Blaauwberg marked the end of Dutch influence at the Cape and the beginning of more than a century of British dominance. What had begun as a naval precaution in the Age of Revolution evolved into a permanent colonial presence. From the granite slopes of Constantia to the windswept plains of Blaauwberg, the echoes of that brief January battle carried far beyond the sound of gunfire into the shaping of a nation, and the long intertwining of empire and wine on Africa’s southern shore.

The Wines of Blaauwberg: Cape Town District, Western Cape

South African Wine Regions and Designations

Modern South African wines are organized under the Wine of Origin (WO) system, established in 1973 to guarantee authenticity of place. It functions much like France’s AOC or Italy’s DOC frameworks, ensuring that what appears on a label truly reflects the land from which it comes. The hierarchy moves from the broad Geographical Unit (e.g., Western Cape) down through Region (such as Coastal Region), District (e.g., Cape Town, Stellenbosch, Paarl, Swartland), and finally to the most specific Ward—often a single valley or hillside known for a distinct microclimate.

The Coastal Region, stretching around Cape Town and north toward Swartland, is the historical and cultural heart of South African viticulture. It was here, beneath the slopes of Table Mountain and the granite ridges of Tygerberg and Constantia, that the Dutch East India Company first planted vines in the 1650s. By the time British and Batavian forces clashed at Blaauwberg in 1806, the surrounding valleys had already produced wines celebrated across Europe.

Terrain and Soil

he Cape Town District, where the Battle of Blaauwberg was fought, lies at the meeting point of the Atlantic Ocean and the African continent—a landscape where sea, sand, and stone converge in striking contrast. To the north of Cape Town, the coastal plain widens into low, wind-swept dunes that once formed the battlefield. From there, the land begins to rise gently inland, giving way to the granite-based ridges of the Tygerberg and Constantiaberg ranges. These hills, climbing from sea level to more than 350 meters, form the backbone of the region’s vineyards, providing slopes of varied exposure and drainage.

Beneath the surface lies a patchwork of ancient geology. The soils are composed of decomposed granite, Malmesbury shale, and isolated bands of Table Mountain sandstone—a combination that yields both structure and subtlety. The granitic soils impart firm minerality, while shale and sandstone contribute texture and balance. Together they create a natural foundation that allows vines to dig deep, moderating vigor and concentrating flavor.

The region’s climate reflects the pull of two oceans. The cold Benguela Current, flowing northward from Antarctica, sends steady breezes across Table Bay and False Bay. These winds cool the vineyards through long summer afternoons, slowing ripening and preserving acidity. The contrast between warm, sunlit days and cool, breezy nights shapes wines of precision and freshness, marked by clarity rather than power.

Grapes Grown

- Whites: Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Semillon, and the historic Muscat de Frontignan of Constantia remain signature varieties. In addition, Chenin Blanc, introduced in the 17th century and locally known as Steen, continues to be an anchor in many Cape blends.

- Reds: Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Syrah (Shiraz) thrive in warmer inland slopes, while Pinot Noir appears in cooler pockets near the sea.

Wines Produced

- Constantia Ward: South Africa’s oldest viticultural area, famed for Vin de Constance, the golden sweet wine made from late-harvest Muscat grapes once served in European royal courts. Today, Constantia also produces elegant Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, and Semillon blends marked by cool-climate freshness.

- Durbanville Ward: Rolling inland hills north of Table Bay yield crisp, grassy Sauvignon Blancs, refined Chardonnays, and supple Bordeaux-style reds. Its high elevations and Atlantic exposure mirror the breezes that once filled British sails offshore.

- Philadelphia Ward: A smaller inland zone producing structured, fruit-driven reds and mineral whites, shaped by shale and granite soils.

- Hout Bay Ward: A rugged coastal pocket with limited plantings but striking maritime influence, crafting boutique Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc wines.

Historical Roots

Viticulture at the Cape began not as a cultural pursuit but as a necessity. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) planted vines in 1655 to supply sailors rounding Africa with fresh provisions and an anti-scurvy ration. The colony’s early governors recognized the potential of Constantia’s granite soils and maritime microclimate, establishing estates that would soon rival Europe’s sweet-wine producers.

In the late 18th century, as Enlightenment Europe erupted into the Age of Revolution, the Cape’s wines became commodities of empire. When Britain seized the colony after the Battle of Muizenberg (1795) and again following the Battle of Blaauwberg (1806), the region’s vineyards shifted into British trade networks. Constantia’s Muscat wines found new markets in London, while the port of Cape Town became a provisioning hub for fleets bound for India and the East.

The same geography that made the Cape indispensable to mariners—its fertile valleys, temperate breezes, and strategic harbors—also made it a natural cradle of wine. Today the Cape Town District stands as both a historic battlefield and a living viticultural landscape, where the interplay of ocean, soil, and empire continues to define South African wine.

Weapon Spotlight: Brown Bess Musket (Land Pattern, 1722–1838)

When British troops advanced across the windswept dunes of Blaauwberg on 8 January 1806, they carried a weapon as familiar to history as to the redcoats themselves—the Brown Bess musket. From Lexington and Waterloo to the Cape of Good Hope, the Brown Bess was the signature firearm of the British Empire, the tool that projected its power across continents during the long wars of the 18th and early 19th centuries.

At Blaauwberg, its steady volleys broke the defensive line of the Batavian Republic (a French-aligned Dutch state) and secured permanent British control of the Cape Colony. On that hot January morning, the disciplined rhythm of the musket’s fire—prime, load, present, fire—echoed across the sand flats north of Cape Town, shaping the outcome of both the battle and South Africa’s future.

The Land Pattern Musket

The Brown Bess—a nickname of uncertain origin but lasting fame—was a .75-caliber smoothbore flintlock musket, about 58 inches long and weighing around 10 pounds. The version carried at Blaauwberg was most likely the India Pattern, a simplified model developed by the East India Company and later adopted by the British Army during the Napoleonic Wars. It featured an iron ramrod, a shorter 39-inch barrel for easier handling, and a sturdy walnut stock designed for mass issue and rough colonial service.

Loading involved biting open a paper cartridge, pouring powder into the pan and barrel, ramming the ball home, and bringing the musket to the shoulder. A trained soldier could deliver three to four rounds per minute, an astonishing rate for the time. Effective range was limited—accurate fire could not be expected beyond 100 yards—but when fired in volleys by disciplined ranks, the Brown Bess became a weapon of psychological and physical shock. Its socket bayonet, permanently affixed during combat, turned each soldier into a dual-purpose musketeer and pikeman.

At the Battle of Blaauwberg

On the open terrain north of Cape Town, precision mattered less than cohesion. The 59th Regiment of Foot and the 93rd (Sutherland) Highlanders advanced in tight formation, pausing only to unleash rolling volleys into the Batavian line. Each burst of smoke and flame from the Brown Bess was part of a deadly cadence: a living machine of firepower perfected by drill and discipline.

The Batavian defenders—fewer in number and supported by mixed militia—could not sustain the exchange. As the British line pressed forward under the rhythmic thunder of musketry, their volleys shattered resistance. Within hours, the Batavian army collapsed, and the Cape was once again in British hands. The victory owed as much to organization and fire discipline as to numbers—and the Brown Bess was at the heart of both.

A Weapon of Empire

By 1806, the Brown Bess had already served Britain for more than eighty years and would remain in use for three more decades. It armed regulars, colonial troops, and East India Company soldiers alike, a constant companion on battlefields from India to the Caribbean. More than any other weapon of its age, it embodied the industrial and tactical doctrine of Georgian Britain—mass production, standardization, and unyielding discipline.

At Blaauwberg, the musket’s presence linked this distant corner of southern Africa to a global conflict that spanned oceans. The same flintlock that fired over the sands of Cape Town would soon roar at Copenhagen, the Peninsula, and Waterloo. In its smoke and recoil lay the echo of an empire expanding by sea and musketry.

Design Legacy: The Lineage of the Brown Bess

The Brown Bess was not a single model but a family of muskets developed through successive “Land Patterns” beginning in 1722. Each iteration refined the same basic concept—a sturdy, smoothbore flintlock that could be produced and maintained on a massive scale.

- Long Land Pattern (1722–1768): The earliest version, with a 46-inch barrel, saw service in the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution.

- Short Land Pattern (1768–1790s): A more compact model, issued during the later colonial wars.

- India Pattern (1793 onward): Introduced for the East India Company and widely adopted during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. This final version accompanied British soldiers wherever the empire marched—from Egypt and the Iberian Peninsula to the beaches of Blaauwberg. Its simple lock, robust stock, and reliability under harsh conditions made it ideal for campaigning across the globe.

By the 1830s, percussion-cap technology rendered the Brown Bess obsolete, but its legacy endured. It influenced the design of early percussion muskets and even the first Minié-type rifles of the mid-19th century. The musket’s very simplicity, handcrafted wood and steel, black powder, and flint, made it the foundation of modern infantry armament.